World’s Fairs, Expositions, and Centennial Celebrations of the Victorian Era, Farm House Museum, Feb-Oct 2024

World’s Fairs, or International Exhibitions, were a formative feature of the late 19th Century. Before 1851, Britain and France held national exhibitions periodically, starting in 1760 in Britain and 1798 in France. These were purely commercial events with the goal of bolstering confidence in the national economy, educating the public and encouraging businesses to innovate and increase competition. These exhibitions grew as time went on, inspiring the beginning of specific exhibitions for industry and art. Before 1928 there was no timetable for the frequency these Fairs were to be put on, no specifications for theme, or size, or regulations at all. In between the main World’s Fairs were industrial exhibitions or smaller international exhibitions all over the world, sometimes multiple times a year.

In 1851, under the leadership of Prince Albert and the Royal Commission for the Exposition, England started a tradition of World’s Fairs built on international participation and educational purposes. Not to be outdone, France eagerly participated and put on their own fairs, helping to grow and develop world’s fairs. These early fairs were very focused on technology and innovation. Art was rarely considered “innovative”, so many fine arts displays were very disappointing.

In 1870, a standard for World’s Fairs took over, one that emphasized the “fair” aspect. The 1867 exhibition in Paris instituted the tradition of individual national pavilions with traditional architecture of the country represented. Restaurants and amusement parks were added to encourage entertainment. These ideas continued into future fairs, growing in size and increasing in cost with each subsequent fair. Unfortunately, the stereotyping and display of foreign nations was also instituted. Live performances of colonial subjects and human zoos relegated certain people as ‘primitive’ and ‘savage’ to the Western citizen. This helped keep many countries under the rule of colonial empires and is important to consider when learning about World’s Fair history, both the good and bad aspects.

There were 11 major World’s Fairs between 1851–1904. Between each major fair, there were smaller exhibitions held in locations across the world. They were much smaller in size, cost, and attendance. They represent the Victorian Era hunger for World’s Fairs and the desire for manufacturers to display their innovation to consumers. Participating in the exhibitions allowed nations to bolster their reputation and project strength in manufacturing and arts. Direct comparisons between nations were inevitable and for those who came out on top, it could bring both economic and diplomatic benefits. Conversely, it could also contribute to negative perceptions about countries, especially for colonized nations. Exhibitors could benefit from sales of displayed items and souvenirs. Even if Fairs weren’t generally profitable, individual exhibitors could certainly find a profit. Winning awards allows for more exposure and was often used in future advertising to show the superiority of a manufacturer’s product.

The World Wars stalled the progress of World’s Fairs and created the need to regulate these exhibitions. The 1928 Paris Convention created the Bureau International des Expositions as the governing body that oversees each World’s Fairs and ensures they follow set regulations. The BIE created a new classification system for fairs. There are World Expos that focus on a universal theme and have the largest scale, Specialized Expos that emphasize a specific theme and are smaller, and Horticultural Exhibits that have specific environmental themes. Today, World’s Fairs on cross-cultural cooperation, promoting quality of life, sustainability, and showcasing new technology and ideas are held every several years.

Expositions were wildly popular attractions and extremely costly to create. Though the first major fairs were in Europe, the trend quickly moved to the US. Through exhibitions, architecture, and access to “far away” or “exotic” cultures, these European and US events became epicenters for the exchange of knowledge, a show of nationalism, and unique innovations through industrialization. Decorative art objects were key catalysts in illustrating to attendees the Victorian ideals, trends, and “best taste.”

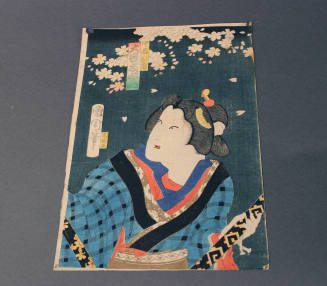

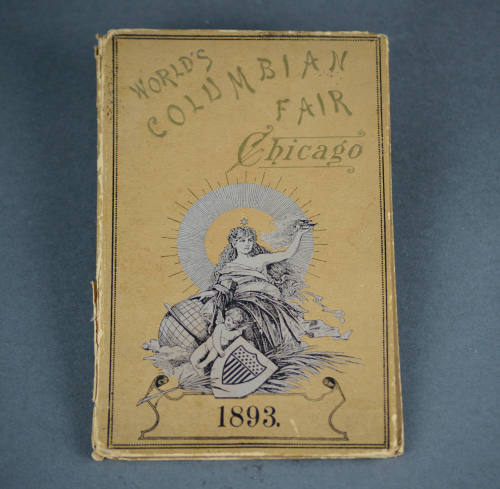

This exhibition illustrates through objects and narrative the earliest World’s Fair in 1851 London, through several in Paris and the Centennial and World’s Columbian Exhibitions in the United States and culminates in the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair. The objects tell the story of how glass, pottery, sculpture, and other arts were innovative for their time and on-trend or trend setters for the movements of the Victorian Era, Japanese influences on Western art, and Art Nouveau. These major public events full of over-the-top fanfare gave access to wide audiences, often millions, while revealing to attendees the peoples and cultures from the furthest of lands.

In the Victorian Era fairs grew exponentially, and the investment was enormous with entire campuses of buildings/pavilions designed and constructed, waterways, fields, gardens, churches, amusement rides, cafeterias, streets and so much more. The buildings were packed with exhibitions from states encouraging tourism, agriculture, companies showcasing their wares, machines, communication innovations, and presentations. Many countries had either their own pavilion or had an area designated to highlight the craft, art, and culture of their native lands, although today we would find many elements of these displays beyond reproach.

Though invention was also a highlight of the Victorian Era fairs – electrification, light bulbs, moving sidewalks, automobiles, blimps, industrialization, new foods like ice cream cones, rides like the Ferris wheel, medical advancements and more – those early fairs highlighted art in many forms. Displays included corn palaces, huge animal sculptures made of odd materials (like almonds), massive statues, paintings, floral displays, and even butter sculptures! Decorative arts firms like Tiffany & Co., Weller Pottery, Rookwood Pottery, Gallé, Gorham, Libby and the Quaker City Glass Co. had entire rooms full of elaborate displays in competition for the Grand Prix award.

The University Museums’ permanent collection includes several objects that were souvenirs of these major events. Souvenirs ranged from booklets, paper fans, buttons, and ribbons, to commemorative glassware and ceramics produced on-site. World’s fair objects and souvenirs remain highly collectible today. The objects help tell the story of the evolution of these major influential events - the good and the bad, the artistic and the functional.

The use of primary source objects of the period allow visitors to this exhibition to evaluate the merits of aspects of the past and learn about how the future of these expos is now focused on entertainment through technological innovation and eco-awareness rather than cultural misappropriation.

This exhibition runs from Feb. through Oct. 2024 at the Farm House Museum and is curated by Gracia Koele, Pohlman Fellow for 2023. Funding for this exhibition and related programming is generously provided by Carol Pletcher and University Museums Membership.