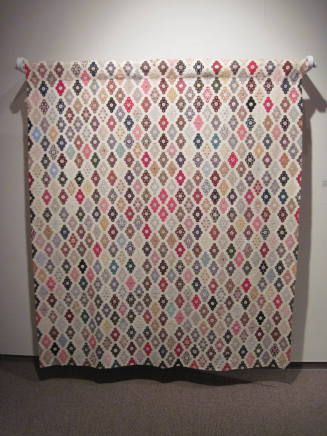

Crazy Quilt

Object NameQuilt

Artist / Maker

Lydia Carver Stark

(American)

Datec. 1881

MediumFabric

Dimensions65 × 65 in. (165.1 × 165.1 cm)

ClassificationsTextiles and Apparel

Credit LineGift of Margaret Johnson. In the Farm House Museum Collection, Farm House Museum, University Museums, Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa.

Object number86.4.1

Status

Not on viewCollections

CultureAmerican

Label TextQuilting represents one of the world’s oldest textile arts, dating back to the ancient world and frequently (though not exclusively) associated with women creators working in their own homes. Since the scraps often came from worn-out clothes, quilts could represent tangible records of family heritage. Female neighbors and friends shared community “quilting bee” time as a cherished social activity. Quilts could be practical and portable necessities, family treasures, and/or luxury folk art. A quilt’s layers provided warmth and padding, while the broad scope of possible compositions allowed the maker to demonstrate her needlework skill and express a personalized flair. Many American quilt patterns involved piecing together blocks of squares, rectangles, triangles, diamonds, or other regular shapes, to form logical, regular designs. By contrast, crazy quilts displayed a riot of hues, mixed fabric types, and unpredictable shapes. During the Victorian era, some women showed off their wealth, leisure, and artistic skill by transforming fine silk or velvet pieces, delicate lace, beads, ribbons, and other costly materials into extravagant crazy quilts meant for decoration, rather than everyday utility. The word “crazy” has many connotations, linking not only to the dense wildness of these designs, but also to the word form “crazed,” referring to the web of fine surface cracks that cover certain types of Japanese pottery and other objects. In its casual sense, the word “crazy” conveys a sense of insanity, and historically, “crazy” women were often victims of medical mistreatment and social abuse. But the crazy quilt is far from insane; though the initial impression may be one of randomness and disorder, arranging odd shapes, bright colors, decorative stitching, and complex fabric patterns for maximally-effective visual impact actually required intense thought and care. In an era before the United States granted women the right to vote or many other opportunities, crazy quilts allowed women to defy the rules of rigid symmetry and experiment with sophisticated novelty, while keeping within the “safe” space of female craftwork. In planning and producing crazy quilts, female masters revealed an impressive sense of color, geometry, playfulness, improvisation, and imagination.

Written by Dr. Amy Bix, Associate Professor, History for the exhibition (Re)discovering S(h)elves.

This quilt won a prize in the Illinois Fair in 1888 (Fair premium is included with quilt). Look for Lydia's signature in square by border. By Lydia C. Stark (American, 1850-1926).

____________

In the Farm House Museum, we are fortunate to have other wonderful examples of one-of-a-kind quilts. The Crazy quilt pictured was handmade in 1881-82 by Lydia Carver Stark (American, 1850-1926). The quilt has a burgundy velvet border with chaotic patchwork shapes of different colors, fabrics, embroidery pieces, appliqué and even some hand-painted pieces. On some Crazy quilts, each piece of fabric has an embroidered image such as an anchor, boys and girls, roses, farm images and others. Large feather stitching links seams between pieces in brightly colored embroidery thread. This particular quilt won a prize at the Illinois State Fair in 1888. Crazy quilts became popular in the U.S. in the late 1800s, likely due to the influence of English embroidery and Japanese art that was displayed at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. The design is abstract and free flowing ignoring the normal block style treatment of traditional quilting patterns.

Locations

- (not entered) Iowa State University, Farm House Museum