Priscilla Kepner Sage

Priscilla Kepner Sage was born in Allentown, Pennsylvania. She grew up with her parents and two siblings in Allentown and Quakertown, Pennsylvania. She received her B.S. in Art Education from Pennsylvania State University in 1958. She pursued graduate studies at Columbia University and Iowa State University, but received her M.F.A. in Sculpture from Drake University in Des Moines, Iowa, in 1981. Priscilla was on the art and design faculty at Iowa State from 1984 to 2000, and taught at Drake University for the previous 18 years. Since her retirement, Priscilla and her husband, Charles, have divided their time between homes in Iowa and Minnesota. Priscilla has two adult children.

I love the interactions of people walking through my sculptures. Art is an expression of the human spirit, and viewers will react to the changing shapes and colors in the context of their own humanity." -Priscilla Sage

SOURCE - https://www.priscillakepnersage.com/index.html (Oct 2025)

The Early Years

Priscilla Kepner Sage grew up in eastern Pennsylvania as one of a long line of quilters. Her parents encouraged her continuous artistic output, enrolling her in adult painting classes while still in elementary school. That is how she spent her time until heading off to Pennsylvania State University in the mid 1950’s where the acclaimed Viktor Lowenfeld was creating the new discipline of Art Education. Lowenfeld emphasized creative thinking, varied styles of learning, and experimenting with diverse materials to find personal expression through the visual arts.

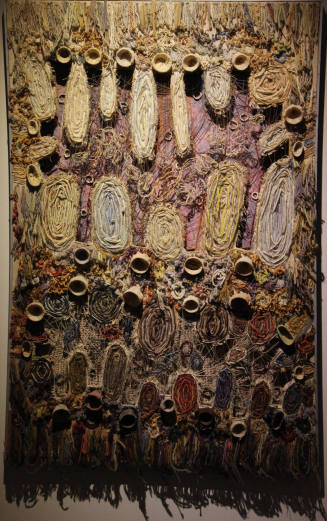

After graduating she discovered New York City and environs during the heyday of Abstract Expressionism. She moved there to teach high school and later to attend Columbia University. Her art from this first period (1959-1969) is greatly influenced by her exposure to the contemporary art scene in New York, particularly to the work of Mariska Karasz, and by her excavations of the Textile District’s refuge. Threads of her Pennsylvania childhood seem to come to the surface merging with her embrace of the city, the innovative methods of Lowenfeld, and her experiences as a painter.

When she leaves in 1962 with husband Charles for Iowa, she brings her innovative new vocabulary of abstract patterns, collaged fabric shapes, and highly textured surfaces of expressive stitched lines with her to the Midwest. Her works like Moon Cave (1965) become more abstract and layered in high relief predicting the first totally three-dimensional sculpture, Silver Mylar (1969).

70s

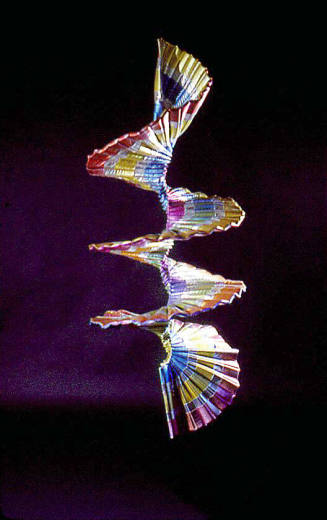

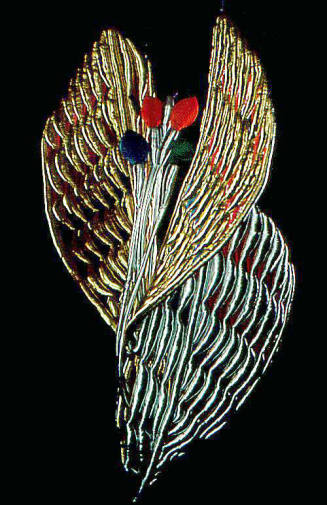

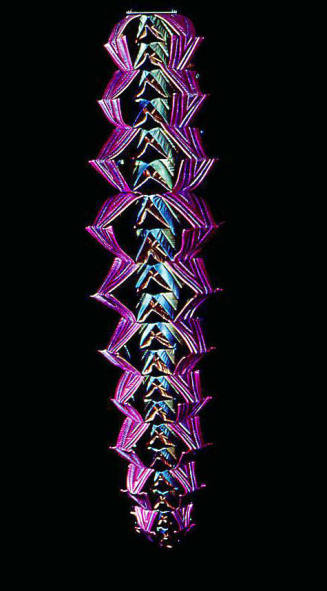

Something important happens in 1969 that predicts the direction of Priscilla’s art in the 1970’s. Silver Mylar takes the scale, verticality and complexity of earlier works and creates a completely three-dimensional abstract being. During the following decade, observation becomes more intense, zooming in on basic structures. Her materials change from everyday fabrics associated with domestic environments to the shiny Mylar metallic fabrics first developed for outer space travel.

Sculptures alternately reference the human body, mechanical objects and botanical forms. The movement and light are palpable. A new bilateral symmetry predicts a shift from the more organic nature of early works to the more geometrically sequenced forms to come. The microcosmic becomes monumental, but also surprising and playful. It is not surprising, then, to learn that Priscilla is at this time the mother of small children as the whimsical kite-like creatures of the Flight Series become airborne.

80s

Clearly the process leading to Priscilla’s most recognized body of public and commissioned works of art comes out of the 1970’s Flight Series sculptures. In the Tinctorial Spiral (1978) and the Candy Spiral (1979) Priscilla discovers the spiral in a myriad of permutations and rotations. During the 1980’s Priscilla connects more directly to geometrical transformation as the basic scaffolding of life forces in both her spiral sculptures and her late 1980’s wall reliefs. Throughout her career, she has a sense of the architecture of natural forms and patterns that, though intuitive, seems also to emanate out of sophisticated mathematical structures in nature.

90’s and 00’s

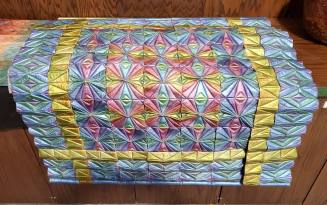

Priscilla returns to the wall in the late eighties and early nineties with a spectacular series of relief quilts, including Kaleidoscopic Reflection I (1989), that go beyond the intricate geometric patterns and colors of the spirals to what amounts to a dazzling tour de force of brilliantly chromatic optical fields.

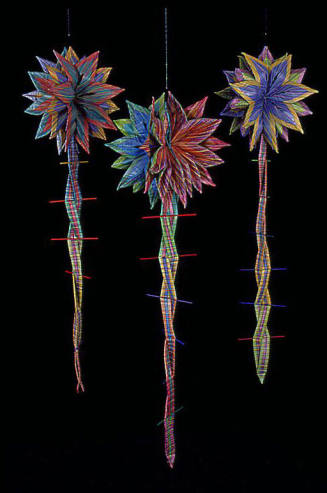

Perhaps inspired by creating and delivering an exhibition of her quilts to Japan in 1993, this propensity for complex optical patterns comes into high relief using padded inter-stitched strips of intensely saturated dyed and painted Mylar. Shapes repeat and reorganize again and again to create glowing geometries that defy one to look away. This complex rhetoric is a kind of code that Priscilla then extends back to into her three-dimensional suspended sculptures. She now glides effortlessly between the wall reliefs and the sculptures.

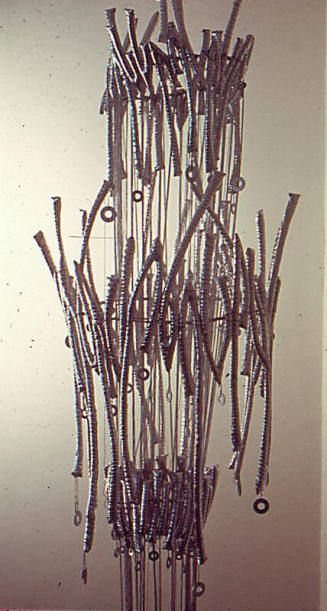

In the suspended sculptures we see and transition from the spiral form into planes of threads and patterns of balancing rods that define magical negative spaces and fold in on themselves when neatly collapsed to the floor. These begin to be created in groups of three or more leading her spectacular installation works of art at the beginning of the new millennium.