Sister Mary Corita Kent

Corita Kent (November 20, 1918 – September 18, 1986), aka Sister Mary Corita Kent, was born Frances Elizabeth Kent in Fort Dodge, Iowa.[1] Kent was an American Catholic nun, an artist, and an educator who worked in Los Angeles and Boston.

She worked almost exclusively with silkscreen, or serigraphy, helping to establish it as a fine art medium. Her artwork, with its messages of love and peace, was particularly popular during the social upheavals of the 1960s and 1970s.[2] After a cancer diagnosis in the early 1970s, she entered an extremely prolific period in her career, including Rainbow Swash design on the LNG storage tank in Boston, and the 1985 version of the United States Postal Service's special "Love" stamp.[3]

Upon entering the Roman Catholic order of Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary in Los Angeles in 1936, Kent took the name Sister Mary Corita.[4] She took classes at Otis (now Otis College of Art and Design) and Chouinard Art Institute and earned her BA from Immaculate Heart College in 1941.[5] She earned her MA at the University of Southern California in Art History in 1951.[6] Between 1938 and 1968 Kent lived and worked in the Immaculate Heart Community.[7] She taught in the Immaculate Heart College and was the chair of its art department. She left the order in 1968 and moved to Boston, where she devoted herself to making art. She died of cancer in 1986.[8]

Her classes at Immaculate Heart were an avant-garde mecca for prominent, ground-breaking artists and inventors, such as Alfred Hitchcock, John Cage, Saul Bass, Buckminster Fuller and Charles & Ray Eames.[9]

Kent credited Charles Eames, Buckminster Fuller, and art historian Dr. Alois Schardt for their important roles in her intellectual and artistic growth.[10]

Kent created several hundred serigraph designs, for posters, book covers, and murals. Her work includes the 1985 United States Postal Service stamp "Love"[11] and Rainbow Swash (1971), the largest copyrighted work of art in the world, covering a 150-foot (46 m) high natural gas tank in Boston.[12]

Some of Corita Kent's most recent solo exhibitions include: Someday is Now: The Art of Corita Kent[13] at the Tang Museum at Skidmore College, There Will Be New Rules Next Week[14] at Dundee Contemporary Arts, and R(ad)ical Love: Sister Mary Corita[15] at the National Museum of Women in the Arts.

Corita Kent's estate is represented by the Corita Art Center, Immaculate Heart Community, Los Angeles, CA.

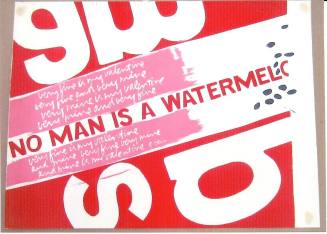

Corita Kent began using popular culture as raw material for her work in 1962. Her screen prints often incorporated the archetypical product of brands of American consumerism alongside spiritual texts. Her design process involved appropriating an original advertising graphic to suit her idea; for example, she would tear, rip, or crumble the image, then re-photograph it. She often used grocery store signage, texts from scripture, newspaper clippings, song lyrics, and writings from literary greats such as Gertrude Stein, E. E. Cummings, and Albert Camus as the textual focal point of her work.[16]

Sister Corita produced her oeuvre during her time at Immaculate Heart College in Los Angeles in response to the Catholic reform in the 1960s by the Vatican Council II as well as several political and social issues happening at the time.[17] Because of her strongly political art, she and others left their order to create the Immaculate Heart Community in 1970 to avoid problems with their archdiocese.[18]

The “Big G” logo that Sister Corita took from General Mills was to stress the idea of ‘goodness’, while the elements stolen from Esso gasoline ads were meant to project the internal power within humans.[19] Unsurprisingly, a Christian subtext does underscore several of her artworks, but not all, which are open to interpretation.[20]

One of Sister Corita’s prints, love your brother (1969), depicts photographs of Martin Luther King Jr. overlaid with her handwritten words, “The king is dead. Love your brother,” outlining one of her more serious artworks, and presenting her views on politics and human nature.[21] Sister Mary Corita’s collages took popular images, often with twisted or reversed words, to comment on the political unrest of the time period, many of which could have been found at any number of marches or demonstrations, some of which she attended herself.[22]