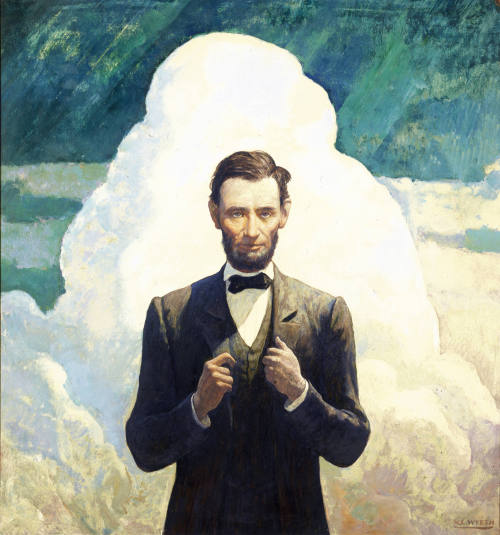

America in the Making: Abraham Lincoln

Object NamePainting

Artist / Maker

Newell Convers Wyeth

(American, 1882 - 1945)

Date1938/1939

OriginU.S.A.

MediumOil on hardboard, (Renaissance Panel)

Dimensions26 3/4 × 24 7/8 in. (67.9 × 63.2 cm)

ClassificationsPaintings

Credit LineGift of John Morrell and Company, Ottumwa, Iowa. In the permanent collection, Brunnier Art Museum, University Museums, Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa.

CopyrightUniversity Museums, Iowa State University prohibits the copying or reproduction in any medium of materials on this website with the following exceptions: Iowa State University students, faculty, and staff for educational use in formal instruction, papers, presentations and projects; limited non-commercial; and personal use that meets the criteria for fair use as defined in the U.S. copyright laws.

Images from the University Museums’ collection cannot be used for publication, apparel/non-apparel merchandise, digital or commercial purposes without prior written permission from the University Museums, Iowa State University. Fair use does not apply to the extent that a license agreement or other contract controls reproduction or other use. University Museums and Iowa State University makes no representation that it is the owner of the copyright of the art object depicted in the photo materials and assumes no responsibility for any claims by third parties arising out of use of the photo materials. Users must obtain all other permissions required for usage of the art object and the photo materials.

For more information, please see http://www.museums.iastate.edu/ImageReproduction.html

Object numberUM83.13

Status

Not on viewCollections

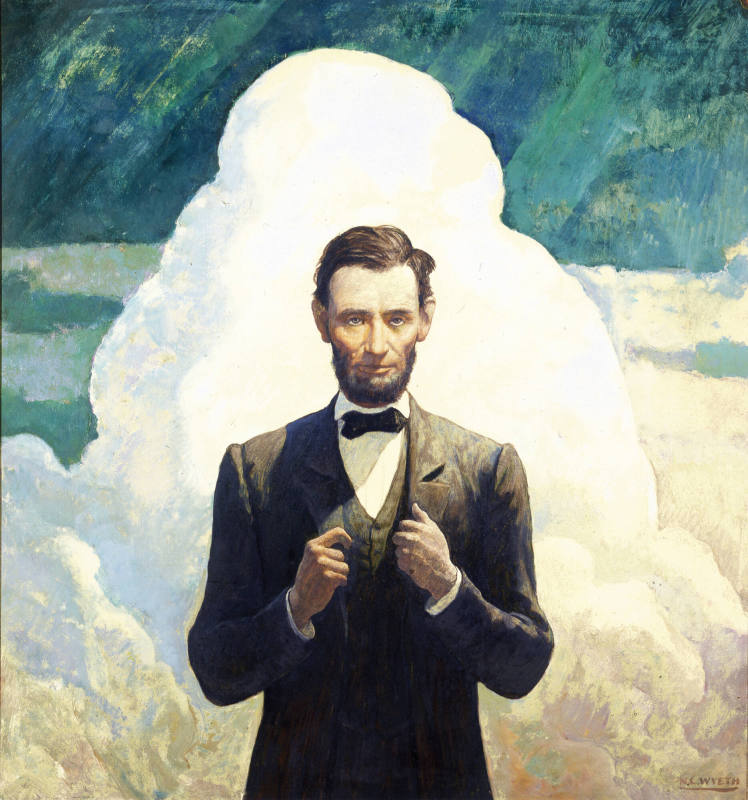

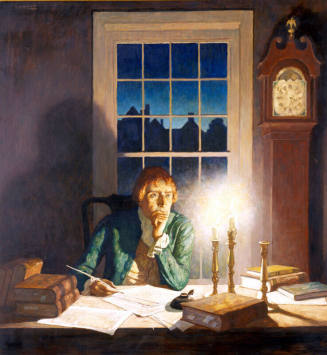

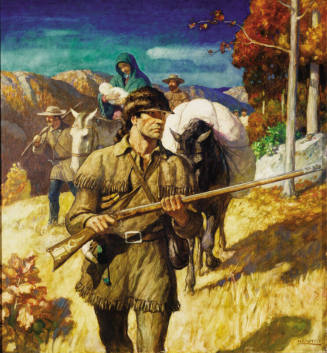

Label TextWyeth’s calendar on America in the Making ends in 1865 with Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) contemplating his second term as President of the United States and the end of the American Civil War (1861-1865). The artist’s series began with the early explorations of the land and then moved through settlement and struggles to establish and define the land as a nation. Three of the paintings relate to gaining our independence (Thomas Jefferson, George Washington at Yorktown, and John Paul Jones), and if Benjamin Franklin is included, fully a third of the paintings deal with figures central to the Revolutionary period. The series ends on a somber note at a time when the nation’s future was far from certain, despite the impending defeat of the South. Wyeth does

not depict an event, but rather a state of mind or perhaps a process of thought, not unlike his image of Jefferson writing the Declaration of Independence. Lincoln, like Jefferson, seems to be peering into the future, contemplating the fate of the nation whose path he has set on a new course. Jefferson’s earliest drafts of the Declaration had included a condemnation of slavery and, though he was himself a slave owner, he recognized it as a moral evil. Lincoln, now, had overseen a bloody war that would advance Jefferson’s assertion that all men were created equal.

The calendar’s caption specifies that this painting has to do with Lincoln’s speech at his second inauguration. His election in 1860 provoked the southern states to secede and soon after his first inauguration in March of 1861, the Confederacy declared itself an independent nation. The Civil War began in South Carolina in April and went on for the next four years. The losses on both sides were enormous: over 600,000 were killed and thousands more wounded, the costliest war ever fought by Americans. The South, where most of the battles took place, was in ruins, and both sides were exhausted, but Robert E. Lee’s army continued to fight. On January 1, 1863, Lincoln had issued the Emancipation Proclamation, freeing all slaves and further alienating the South. Though a Northern victory seemed certain in March of 1865 when his second term began, the issues that had caused the war were not truly resolved, as Lincoln understood. Embarking on his second administration, he was personally weary and burdened by the certainty that the nation, though the Union had been preserved, faced deep and serious divisions.

As his new term of office began, he knew that his speech could set the tone for a Northern victory, and at the same time a Southern defeat, with the daunting task of re-uniting an embittered land. Lincoln did not absolve the South and its defense of slavery, and he emphasized that slavery could no longer be tolerated, but he also recognized that forbearance was called for in order to “bind up the nation’s wounds.”1 He recognized that both sides “read the same Bible and pray to the same God” while he wondered if “this mighty scourge of war” was not God’s punishment on all for the “two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil” born by the enslaved Americans. He must have weighed each word carefully as he composed an address that he hoped would prepare the nation for a difficult reconciliation. Wyeth’s painting suggests both sadness and the resolution of Lincoln’s mind in the closing days of the war.

This painting focuses entirely on the half-length figure of Lincon, standing with head slightly bent downward, but eyes directed toward the viewer. His environment already seems to be the province of history, and Wyeth may have had in mind the long history of cloud-strewn images of the apotheosis as heroes enter the ranks of the divine. Lincoln’s life ended on April15, 1865 just six days after Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox, Virginia and within a month of having delivered his second inaugural address. The weight of these historical events seems embodied in Lincoln’s expression though, by lifting his portrait into the skies amidst the billowing clouds, Wyeth also implies the president’s enshrinement as an American martyr. Lincoln’s pose, holding the lapels of his coat and head thoughtfully turned downward, may have been derived in part from the standing portrait sculpted by Augustus Saint Gaudens (1848-1907) and installed in Chicago’s Lincoln Park in 1887. The tone of this painting is decidedly different from the others in the series. Even the rather brooding character of the portrait of Jefferson does not seem to assume the emotional weight carried here by Lincoln. This is the only image in which there is an implication of genuine sadness or tragedy. The grave effect of the painting canhardly be separated from the psychological and spiritual situation of Abraham Lincoln as he tried to hold together a nation rent asunder by the crime of slavery. It is the only painting in which Wyeth hints at a national culpability in the mistreatment of some of its citizens.

Lincoln was the artist’s subject on other occasions. Among his earliest portraits of the sixteenth president had been an illustration for an American history schoolbook, showing Lincoln delivering his second inaugural address, surrounded by his cabinet.2 Wyeth used the book commission to read extensively on Lincoln and to ponder how he might be presented, as the artist described in a letter. “I worked this morning, putting the finishing touches upon my conception of Lincoln – reading his second inaugural address....It was an interesting task and gave me my first opportunity to interpret Lincoln. Being for a school history I had to be rather conservative. Would like it better if I had felt free to seek for more of an impressionistic result, but dared not do it on this canvas. I get considerable pleasure painting pronounced character heads.”3 His next image of Lincoln, a 1922 mural for the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, did give him more latitude for interpretation. Wyeth continued to depict his subject standing, but now amidst the burdens of office as he consults with his Secretary of the Treasury, Salmon P. Chase (1808-1873). While the conversation may be ostensibly about financial matters, perhaps funding for the Civil War, the gravity of Lincoln’s expression and demeanor suggests that his mind is dwelling on the desperate matters of life and death brought about by the war. Once again in a letter, Wyeth explained how thoroughly he acquainted himself with Lincoln’s life and his appearance. “I have recently read three of the ten volumes of Nicolay and Hay’s history of Lincoln, also several other books dealing with his domestic and official life in the

White House, besides numerous accounts of his appearance, personality, etc., all particularly related to the early Civil War period. Have studied numerous photographic portraits of the man and also of Chase so that now I feel fairly saturated with their physical appearances, the sound of their voices, their complexities and their characteristic movements, both bodily and facial.”4 For this painting, Wyeth’s tax records indicate that he rented a coat, hired a model, and purchased photographs of Lincoln and a cast of the life mask taken by sculptor Leonard W. Volk in 1860.5

For his final painting in America in the Making, Wyeth chose to separate Lincoln from any but the most ethereal environments while preserving an acute observation of a man aware of the carnage of war, but possessing the determination to see it through. In Wyeth’s picture is a dual sense of Lincoln having presided over the most dreadful period of our national history and yet, by doing so, preserving the Union and accomplishing a moral victory. We do not know exactly who chose the episodes from American history in the 1940 calendar nor why Wyeth interpreted them as he did. It is difficult, however, not to think that his decisions were colored by the near certainty that the nation was about to be engulfed in another conflict of terrible dimensions, and one with moral consequences. Just as Lincoln believed that the nation could not endure half slave and half free, many saw the Nazism of Germany, the Fascism of Italy, and the militarism of Japan as a threat to the foundations of civilization itself. The soberness and sense of foreboding in the Lincoln picture was shared by many Americans who watched the conflict growing ever closer to home.

ENDNOTES

1 Lincoln’s second inaugural address is widely available. One online source is via the Library of Congress on the website of the Avalon Project: http://www.loc.gov/teachers/newsevents/events/lincoln/pdf/avalonInaug2.pdf.

2 Long, William J., America, A History of Our Country, Boston: Ginn and Co., 1923, opp.336; cited in Podmaniczky, 379.

3 Podmaniczky, 379-380.

4 Wyeth to his mother, July 15, 1921; quoted in curatorial comments in Podmaniczky, 602; M 13 (330).

5 The cast of Lincoln’s mask and many photographs of Lincoln remain in the Wyeth studio collection. Notes on tax records provided by Podmaniczky

Locations

- (not entered) Iowa State University, Brunnier Main Storage

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938/1939

Object number: UM83.19

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938

Object number: UM83.14

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938/1939

Object number: UM83.18

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938/1939

Object number: UM83.17

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1939

Object number: UM83.15

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938/1939

Object number: UM83.21

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938

Object number: UM83.20

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938

Object number: UM83.16

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938

Object number: UM82.120

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938/1939

Object number: UM82.121

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1939

Object number: UM90.53