America in the Making: Sam Houston

Object NamePainting

Artist / Maker

Newell Convers Wyeth

(American, 1882 - 1945)

Date1938

OriginU.S.A.

Mediumoil on hardboard (Renaissance Panel)

Dimensions26 3/4 × 24 7/8 in. (67.9 × 63.2 cm)

ClassificationsPaintings

Credit LineGift of John Morrell and Company, Ottumwa, Iowa. In the permanent collection, Brunnier Art Museum, University Museums, Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa.

CopyrightUniversity Museums, Iowa State University prohibits the copying or reproduction in any medium of materials on this website with the following exceptions: Iowa State University students, faculty, and staff for educational use in formal instruction, papers, presentations and projects; limited non-commercial; and personal use that meets the criteria for fair use as defined in the U.S. copyright laws.

Images from the University Museums’ collection cannot be used for publication, apparel/non-apparel merchandise, digital or commercial purposes without prior written permission from the University Museums, Iowa State University. Fair use does not apply to the extent that a license agreement or other contract controls reproduction or other use. University Museums and Iowa State University makes no representation that it is the owner of the copyright of the art object depicted in the photo materials and assumes no responsibility for any claims by third parties arising out of use of the photo materials. Users must obtain all other permissions required for usage of the art object and the photo materials.

For more information, please see http://www.museums.iastate.edu/ImageReproduction.html

Object numberUM83.14

Status

Not on viewCollections

Label TextThe brilliant victory at the Battle of San Jacinto in 1836 was a high spot in the colorful career of Sam Houston. Texas was made independent thereby, with Houston as its first president. After its admission to the Union, Houston became senator and then governor. He was an able soldier and a legislator of rare foresight.

Most of Wyeth’s paintings for his 1940 calendar are about the exploring or acquisition of land, or about independence in some regard. Sam Houston deals with both in that the Battle of San Jacinto did secure Texas’s independence and eventually led to its statehood in 1845 and, with it, an enlargement of the United States. In the 1820s, the newly

independent nation of Mexico began encouraging the settlement of the part of its territory now known as Texas. Settlers from across the Mississippi River in the United States eagerly established homesteads and their numbers quickly grew, but so did the tension between them and the Mexican government.1 By 1835, these Texians (as they were

then called) had organized sufficient resistance that Mexico sent its army, under General Santa Anna, to quell the Texas Revolution. In early 1836, the army besieged a fort near San Antonio, the Alamo, and when the Texians would not surrender, overcame the fortress and killed all its defenders on March 6. Included among the dead were frontier legends such as David Crockett, Jim Bowie, and Col.William Travis. A few weeks

later, on March 27 near the town of Goliad, Santa Anna ordered the execution of over three hundred Texian prisoners of war.2 These two events galvanized determination for Texas independence, and an army rallied under the command of Sam Houston (1793-1863).

Declining to engage Santa Anna’s army immediately, Houston brought his fighters

to an area along the San Jacinto River (now within the city of Houston) while the pursuing

Mexican army encamped not far away. As the Mexicans considered their next assault,

Houston ordered a bridge burned so that Santa Anna was entrapped and then, without waiting for the much larger army to bring its attack, he organized his troops “without,” he recalled, “exposing our designs to the Enemy.”3 On April 21, 1836, the Mexican army had not posted sentries and was at their mid-day rest when the Texians burst from their hiding places in a ferocious charge into the somnolent Mexican camp. Shouting their battle cries of “Remember Goliad” and “Remember the Alamo,” they quickly defeated their opponents, as Houston described: “advancing in double quick time, [his men] sung the war cry ‘Remember the Alamo.’...The conflict lasted about 18 minutes from the time of close action, until we were in possession of the Enemy’s [encampment].”4 In his recollection of the quick, but very intense battle, Colonel Pedro Delgado of the Mexican

army wrote that the Texians “advanced resolutely upon our camp...[and] meeting no

resistance they dashed, lightning like upon our...bewildered and panic-stricken...camp.”5

Of Santa Anna’s army, Houston estimated that 630 were killed, while the losses for Texas were nine men.6 In his report on the battle, Houston recalled that his men were ready for a fight. “[Our] troops paraded with alacrity and spirit and were anxious for the contest – Their conscious disparity in numbers only seemed to increase their confidence, and heightened their anxiety for the conflict.”7 Texas had declared its independence in March of 1836, but after Houston’s victory, it became truly independent, establishing the Republic of Texas, with Houston as its president.

Born in Virginia, Houston grew up in Tennessee where he lived for a time with the Cherokee. In 1813, he joined the Army and attracted the admiration of fellow Tennessean, Andrew Jackson (1767-1845), who would become the seventh president of the United States. Houston embarked upon a political career, becoming the Attorney General for Nashville, then a two-term Representative in Congress (1823-1827), and finally the governor of the state in 1827. He served two years before a scandal over his failed marriage led him to resign his office and move to the Cherokee Nation in Oklahoma. He

relocated to Texas in 1835 on the eve of theTexas Revolution in which his army experience and his leadership skills would be employed. After his San Jacinto triumph, he was elected the first president of the Republic (1836-1838). During a second term as president (1841-1844), he prepared Texas for the transition from independent republic to statehood. Through the annexation of Texas (which included areas now in the states of Oklahoma, New Mexico, Colorado, Kansas, and Wyoming) in 1845, the land of the United States was significantly expanded. Houston served in the Senate from 1846 until 1859, when he was elected governor of Texas (making him the only person to have been governor of two states). When the calendar caption praises him as a “legislator of rare

foresight,” it may be referring to his attempts while in the Senate to find justice for Indians

and limit the expansion of slavery in the years just before the Civil War. In 1854, he was the only southern Democrat who voted against the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which allowed territories to vote on the issue of slavery, provoking the Texas legislature to recall him in 1857. Elected governor once again, in 1859, Houston counseled his state against secession, but when the voters decided to secede from the Union and Houston

was expected to take an oath of loyalty to the Confederacy, he resigned his office.

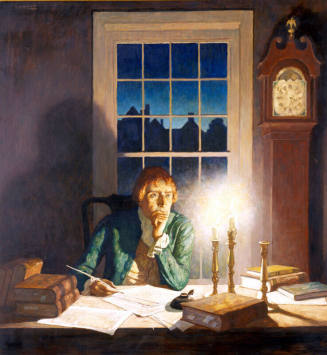

Wyeth’s depiction of Houston shows him not as a statesman or even as the wily military strategist who led Santa Anna into a trap and defeated him in a humiliatingly short time. In this painting, Houston is the fiery, impassioned leader who directed the anger of Goliad and the Alamo into a focused military action. Inciting his men to “Remember the Alamo,” Houston himself led the charge, as one of his fellow commanders testified. “Gen. Houston acted with great gallantry encouraging his men to the attack and herocially [sic] charged in front of the Infantry within a few yards of the enemy receiving at the same time a wound in his leg. The enemy soon took flight.”8 Wyeth’s depiction of the single line of the attack is verified in several accounts, including that of one of Santa Anna’s generals, who remembered, “I saw that their formation was a mere line of one rank, and very extended.”9 In Wyeth’s painting, Houston is the mounted commander at the head of

this assault, his wild-eyed horse like an arrow springing into combat, and his foot soldiers

leaning sharply forward as they run toward the enemy lines. His finger pointing forward,

Houston twists in the saddle as he shouts back at his troops, surely leading the cry of

“Remember the Alamo.” The blonde man in the foreground, with his long rifle clutched in his hands, seems to be joining in the shout, as do other fighters along the line. In no other painting from this series does Wyeth depict such strong emotions in his subjects; even John Paul Jones brandishes his sword with less ferocity. Perhaps the artist was affected by accounts of the battle that emphasize the intense anger of the Texians toward the Mexican army which had dealt them so many devastating blows and had, from

the Texas perspective, committed murder. The 76 N.C. Wyeth’s America In the Makingpace of events in Texas was quite fast during their Revolution’s engagement with the Mexican army; the memory of the Alamo and Goliad was vivid, and it still possessed the sting of immediacy. The fury of these Texas fighters is clearly displayed in

Wyeth’s painting and can even be noticed on the faces of men well into the distance. The dynamism with which they all lean into their line’s advance and level their weapons furthers the sense of the violence of the coming combat.

As in other pictures for America in the Making, Wyeth paints clouds in the sky and clouds of dust or smoke that help dramatize his narrative. A bank of clouds (mixed with some smoke?) occupies the upper left until it separates to form a sort of reverse

arrow, or wedge, which echoes the shape of Houston’s hat. The opening between the two arms of the cloud formation isolates and emphasizes his straight arm and pointing finger. As noted above, Houston is by far the most dynamic figure in the series; in the battle scenes, John Paul Jones is in the thick of a fight, but he is planted firmly on deck while Washington observes his battle from a hillside. This picture is also the most eccentric

composition, with all of the action emerging boldly from the left and the large, dominant figure of Houston on his striding horse almost in mid-air. This compositional device of having all the action burst from one side with the lead figure bounding into the center of the picture fosters the idea of the angry resolution of the Texians confronting the

much larger army of Mexico.

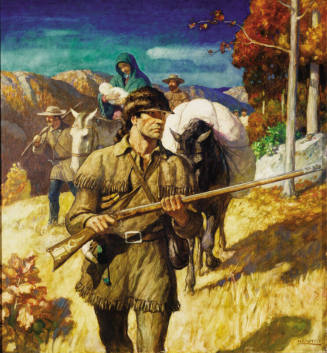

Wyeth’s records indicate costs for costumes and research trips to the library in Wilmington. The men of Houston’s army are not shown in uniform, but in the stock frontier costumes that the artist used in numerous paintings. Though some of the

fighters in the Texas Revolution did have uniforms, many Texians were not army regulars and wore their own clothing. The preparatory drawing for Sam Houston, typical of Wyeth’s practice, is nearly identical to the finished painting except that the drawing contains a solid cloud bank behind the figure of Houston.

ENDNOTES

1 One of the areas of disagreement involved slavery, which continued and increased in Texas though it had been officially abolished by the Mexican government in 1829.

2 Estimates of the number murdered at Goliad vary somewhat, but some prisoners did escape to relay the news of the Mexican crime against the Texian prisoners of war. For information on this and other topics of Texas history, see the website of the Texas

State Historical Association: http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/qeg02.

3 “Sam Houston’s Copy of His Official Report of the Battle of San Jacinto.” In describing his strategy in the report he submitted to the acting president of the nascent Republic of Texas, David S. Burnet, on April 25, 1836, Houston wrote that he had “ordered the Bridge on the only road communicating with the Brazos, distant 8 miles from our Encampment, to be destroyed, thus cutting off all possibility of escape.” Then, he added, “Our situation afforded us an opportunity of making the arrangements preparatory to the attack without exposing our design to the Enemy.” This report and other sources for Houston are found on the website of the Texas State Library and Archives Commission, at

http://www.tsl.state.tx.us/treasures/republic/san-jacinto/report-04.html. In all quotations, the original spelling, punctuation, and other characteristics have been retained.

4 “Sam Houston’s...Report.”

5 “Description of the Battle of San Jacinto by Colonel Pedro Delgado, Member General Santa Anna’s Staff,” reprinted on website of Texas A&M University from Linn, John J., Fifty Years in Texas, 1883; http://www.tamu.edu.faculty/ccbn/dewitt/delgadosanj.htm.

6 “Sam Houston’s...Report.” One of Houston’s soldiers recalled the battle this way: “In twenty Minutes We had them on the run and before the Sun went down we Streched eight hundred of [them] on the field never to rise, again” Lyman F. Rounds: Pension

Application. http://www.tsl.state.tx.us/treasures/republic/san-jacinto-rounds-account.html.

7 “Sam Houston’s...Report.”

8 “Sam Houston’s copy of Secretary of War Thomas J. Rusk’s Official Report of the Battle of San Jacinto,” April 22, 1836. http://www.tsl.state.tx.us/treasures/giants/sj-rusk-03.html.

9 Delgado.

Locations

- (not entered) Iowa State University, Brunnier Main Storage

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1939

Object number: UM83.15

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938

Object number: UM83.16

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938/1939

Object number: UM83.17

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938/1939

Object number: UM83.18

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938/1939

Object number: UM83.19

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938/1939

Object number: UM83.21

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938

Object number: UM83.20

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938/1939

Object number: UM83.13

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938

Object number: UM82.120

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938/1939

Object number: UM82.121

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1939

Object number: UM90.53

Object Name: Drawing

Frank Miller

1971

Object number: UM83.128