America in the Making: George Washington at Yorktown

Object NamePainting

Artist / Maker

Newell Convers Wyeth

(American, 1882 - 1945)

Date1938/1939

OriginU.S.A.

MediumOil on hardboard (Renaissance panel)

Dimensions26 3/4 × 24 7/8 in. (67.9 × 63.2 cm)

ClassificationsPaintings

Credit LineGift of John Morrell and Company, Ottumwa, Iowa. In the permanent collection, Brunnier Art Museum, University Museums, Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa.

CopyrightUniversity Museums, Iowa State University prohibits the copying or reproduction in any medium of materials on this website with the following exceptions: Iowa State University students, faculty, and staff for educational use in formal instruction, papers, presentations and projects; limited non-commercial; and personal use that meets the criteria for fair use as defined in the U.S. copyright laws.

Images from the University Museums’ collection cannot be used for publication, apparel/non-apparel merchandise, digital or commercial purposes without prior written permission from the University Museums, Iowa State University. Fair use does not apply to the extent that a license agreement or other contract controls reproduction or other use. University Museums and Iowa State University makes no representation that it is the owner of the copyright of the art object depicted in the photo materials and assumes no responsibility for any claims by third parties arising out of use of the photo materials. Users must obtain all other permissions required for usage of the art object and the photo materials.

For more information, please see http://www.museums.iastate.edu/ImageReproduction.html

Object numberUM83.17

Status

Not on viewCollections

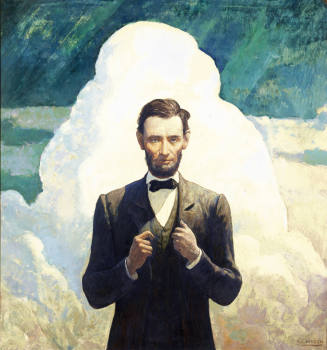

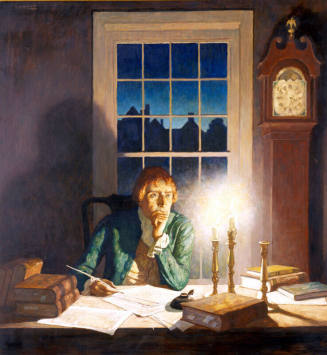

Label TextThe fall of Yorktown – October 19, 1781 – was the deciding victory in America’s war for independence. The painting shows General Washington looking toward Yorktown; behind him is Rochambeau, whose co-operation made victory possible. The ships of DeGrasse lie in the York River, and an English vessel is burning.

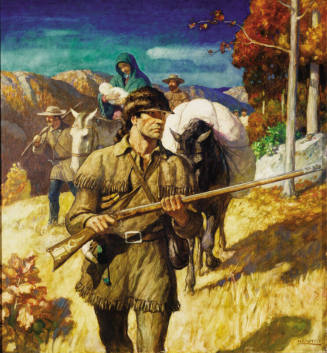

Wyeth’s scene here is a truly decisive one in America in the Making for it depicts the final major battle in the Revolutionary War. The war for independence began in 1775 and technically, did not end until 1783 when the Treaty of Paris was signed. The military campaigns on both sides, however, culminated with the surrender of British forces after the Battle of Yorktown (sometimes called the Siege of Yorktown) in 1781. George Washington (1732-1799), commander of the Continental Army, had persevered since 1775 with his often ill-equipped and ill-paid men, but the colonial forces had been unable to achieve a clear victory that would bring to reality the Declaration of Independence. By 1778, France had joined the American effort against their common enemy, the British, and began providing financial aid and military forces to the colonials. There was considerable sympathy in France for the revolutionary cause of the Americans, and one French nobleman, the Marquis de Lafayette (1757-1834), enlisted on the staff of General Washington in 1777 and aided in securing the American military victory.

In 1781, a combined force of Americans under Washington and French under the Comte de Rochambeau (1725-1807) anticipated a battle in New York until Washington was persuaded by his own staff and Rochambeau that the chances of finally defeating the British were greater in the south. In August, their forces marched to Virginia where they merged with Lafayette’s, which had been containing the British southern army led by Lord Cornwallis (1738-1805) to the area around Yorktown. They expected to engage his army which also held the important coastal area of the Chesapeake Bay, but to do so, they needed naval support. By early September, the French Navy, led by the Compte de Grasse, arrived at the Bay and drove off the British ships which were supplying Cornwallis’s army, leaving him stranded and without access to reinforcements. The French and the Americans then began the siege at Yorktown in late September, bombarding British lines and gradually extending their own fortifications. The final battle began on October 14, 1781, with the colonials and their allies advancing and the British defending increasingly limited positions. On October 16, Cornwallis tried to evacuate his army across the Bay into Maryland (since DeGrasse’s ships continued to blockade the route to the Atlantic Ocean), but only one ship of soldiers and wounded made it across before storms doomed any further hope of escape. By the morning of October 19, it was evident that Cornwallis’s army had been defeated, and he surrendered. He did not himself go out to meet the victors but, saying that he was ill, sent another officer, who offered his sword to the French commander, Rochambeau. Rochambeau refused it, indicating instead that the symbol of the British defeat should be offered to the American, General Washington.1

Most illustrations of the Revolutionary War depict the surrender itself when the British had to walk between two lines, French on one side and Americans on the other, as the formal ceremony took place. John Trumbull’s painting in the rotunda of the Capitol in Washington D.C., The Surrender of Lord Cornwallis of 1820, is probably the most famous image of the war’s end. Wyeth, however, chose a scene before the victory was secured which emphasized the role of Washington and his French compatriot as strategizers and commanders. Washington stands looking northward with Rochambeau nearby, both men holding spyglasses in order to better observe the action. The caption for the calendar page mentions the actual day of surrender, October 19, but it is possible that the artist is depicting an earlier point in the battle.2 The battle was won by assaulting the redoubts the British built against the armies surrounding Yorktown and then by advancing the French/American lines by building fortifications through the ground that had been gained. The wooden planks on which the generals stand may delineate the edge of a trench from which their troops could fire. As the terrain dips in front of the generals, Wyeth included two forms that could be fencing but could also suggest the abatis (sharpened wooden poles) and other materials used in the fortifications. In the middle ground, a whitish cloud-like mass likely indicates smoke from the bombardment or from the assault on the British redoubts. The geography in Wyeth’s picture of the Battle of Yorktown is generally correct, in that the French and American lines were along the southwestern side of the York River while the British were entrenched closer to the river’s bank.3 The small town is sketchily indicated along the shore. From his position at the mouth of the river where it empties into Chesapeake Bay, DeGrasse had the British blockaded and, by including a burning ship, Wyeth commemorated the French naval role in the American victory. He may also have been referring to the French bombardment of October 10 which set fire to the British ship HMS Charon.

As an illustrator, Wyeth had been trained to find the most dramatic aspect of any story. Yet, as already pointed out, he told his son that he wanted to make his own distinctive contribution to the story and find something that had not already been described or, in the case of George Washington’s victory at Yorktown, over-described. Washington here is not directly in combat (though his men often were concerned at how close he came to the fighting) but is shown observing the battle. More importantly, his focus is on the actions taken at his direction, assessing his own commands and, we can imagine, contemplating his next move. Both generals are fully engaged in following the course of the battle, but Washington’s pose is a less passive one. With one foot planted forward, an arm held at his hip, and his head turned decisively toward the distant fight, he exudes a certain bravado and heroicism. The drama here is not so much the battle itself, which is hardly depicted at all, but in the almost mythical gallantry and courage of the man who would be called the father of his country. Wyeth implicitly praises Washington’s character and the force of intellect and integrity that maintained him during the long years when the war’s outcome seemed not at all certain. His physical strength, his emotional fortitude, and his military acumen all portray a man who could lead the often rough and undisciplined American revolutionaries toward a national resolution and then, a few years later, help the colonies coalesce into a true nation. His diplomacy in enlisting the aid of the French, a major world power, and his ability to inspire their confidence in his leadership is also intimated in Wyeth’s image. Still and steadfast, the figure of Washington takes on the effect of an heroic statue.

The artist uses several compositional devices to emphasize Washington. The primary one is simply placing his subject well into the foreground and disposing the light, coming from the west, onto the facial profile and along the right side of the body. The two lines of the wooden, fence-like forms converge into an arrow that follows along the crest of the hill to point to Washington. The line of the long planks comes from the right background and stops beneath his boots. As noted, the general is static, and the figure of Rochambeau behind him is even more so. Only the sketchily painted men at the cannon are in motion. The sense of activity, of a battle being fought, is conveyed almost entirely by the whitish clouds and plumes of smoke that issue from the cannon, the bombardment (or fighting) taking place below the crest of the hill in the middle ground and the broad dark line emerging from the burning ship along the horizon line. Both the ground, combat and the burning ship produce clouds that drift compositionally in the direction of Washington, with the smoky plume positioned directly behind his head.

Wyeth painted at least a dozen works that included George Washington, most of which depict Washington as the central subject. The artist’s 1940 calendar illustration was the only one that recorded an actual battle (perhaps a harbinger of the approach of World War II) though several depict him as a military commander, as did Wyeth’s first picture of him, Beginning of the American Union, Washington Salutes the Flag as he Takes Command of the Continental Army at Cambridge, 1775, painted in 1919.4 Three paintings depict the struggles that Washington endured with his troops, cementing his reputation for perseverance and earning the regard of his Revolutionary soldiers. A 1928 painting shows him crossing an ice-choked Delaware River in an open boat while above (and certainly not acknowledged by Washington) floats an allegorical, light-suffused figure of victory. Much grimmer and more realistic scenes reflect the despair and suffering of the Continental Army in the Valley Forge winter of 1777-78. In Washington Reviewing his Troops (1922), the General walks along in front of a formation of his soldiers, standing at attention in a snowstorm and barely bundled against the cold. Winter at Valley Forge, 1934/36 displays a group of soldiers gathered around a fire, singing, and apparently trying to cheer themselves up while off to the side in the snowy landscape stands a grave Washington, wrapped in a cloak against the winter wind and unable to join in the merriment.5 Other paintings celebrate Washington’s subsequent service to the nation as well as his legacy of fighting stalwartly on despite the odds.6

Wyeth’s most striking and personal painting involving Washington is In a Dream I Meet General Washington of 1930.7 It was not a commercial commission and was painted because of a vivid dream the artist had, as his title clearly explains. He had been working on a mural of Washington being received joyously in Trenton, New Jersey as he journeyed to New York to become the first president of the United States. Wyeth nearly had a serious fall from the scaffolding and, that night, he dreamed he was painting when Washington appeared and rode his horse right up to the artist. The general began to narrate the Battle of Brandywine, which had been fought near Wyeth’s home at Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania in 1777, as it progressed right in front of them. Lafayette was part of the scene as was Wyeth’s young son, Andrew, while soldiers marched past and canon fired. Wyeth’s painting stacked one dream incident on top of the other in a fantasy composition that is distinctive in his career. It may suggest the identification that he developed with subjects which truly intrigued him. His last painting before his death in 1945 was of Washington, First Farmer of the Land.8

Wyeth’s records regarding the painting of Washington at Yorktown indicate that he hired models, bought or rented costumes, and also purchased a life mask of Washington.9 The costume in the Yorktown painting is a dark blue coat with golden yellow trim (and perhaps lining) along with light-colored trousers and is similar to that worn in other Wyeth paintings of Washington.10 Photographs of his studio at Chadds Ford show a portrait bust and a tri-cornered hat such as that found in most of the paintings.11 As noted earlier, Wyeth expensed a two-day trip to Yorktown, surely in part to understand the terrain on which this crucial battle was won.

ENDNOTES

1 When offered the British sword, Washington also refused it and, instead, directed that it be presented to General Benjamin Lincoln (1733-1810), who had been forced to surrender the city of Charleston, South Carolina earlier in the war.

2 The surrender took place around 9:00 on the morning of October 19. The light in the picture comes from the west, and since the general geographic orientation of the scene is accurate, it suggests that Wyeth’s scene is in the afternoon.

3 According to Wyeth’s tax records for this picture, he spent $50 on a trip to Yorktown. Perhaps his purpose was to ensure that his depiction of the battle site was geographically accurate.

4 Beginning of the American Union, Washington Salutes the Flag as he Takes Command of the Continental Army at Cambridge, 1775 was painted around 1919 as an illustration for Long, William J., America, A History of Our Country (Boston: Ginn and Co., 1923). Podmaniczky, 379, I 742 (592).

5 Washington Crossing the Delaware, 1928, is a study for a mural that was never executed; Podmaniczky, 618, M 42 (2242). Untitled (Washington and his Men Around a Winter Campfire), 1929/30; Podmaniczky, 660, C 70 (1353), is related to Winter at Valley Forge, 1934/36; 669, C 98 (1104), which was painted as a calendar illustration for the Home Insurance Co. of New Jersey. Washington (Washington Reviewing His Troops; Washington Reviewing the Troops), 1922 was used as an illustration for Matthews, Brander, Poems of American Patriotism (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1922), Podmaniczky, 436, I 902 (776).

6 Washington and Statue of Liberty, 1922; Podmaniczky, 434, No. I 897 (775), used as the title page for Poems of American Patriotism. The Hamilton Mural (Alexander Hamilton Addressing George Washington and Robert Morris), 1922; 601; No. M 12 (798), a mural now at the Langham Hotel in Boston. Reception to Washington on April 21, 1789, at Trenton on his way to New York to Assume the Duties of the Presidency of the United States, 1930; 618, M 44 (1076) and its study, M 43 (1122). Building the First White House (Building the “President’s House”), c.1931, 662-3, C 76 (1085), painted for use as a poster for the Pennsylvania Railroad and now unlocated. George Washington (America Must Go Forward; Forward, America!), 1931; 663, C 77 (1145), originally painted as a poster for Strawbridge and Clothier and used as a 1941 calendar illustration for the New York Life Insurance Co. Wyeth also painted a sign (Washington’s Headquarters) for a friend in Chadds Ford whose house had reportedly been a headquarters for Washington; 1919, 834, O 7 (2483) and a sign for a local barbershop that read “This is the place where Washington and Lafayette had a close shave.” 835, O 9 (1171).

7 In a Dream I Meet General Washington (In a Dream I Saw General Washington; Washington at Brandywine), 1930; Podmaniczky, 815, P 33 (201). The painting won the Clark Prize at the Corcoran Gallery of Art exhibition in 1932.

8 First Farmer of the Land (Washington the Farmer), 1945; Podmaniczky, 593-94, I 1322 (1117), used as an illustration for the magazine Country Gentleman.

9 Podmaniczky noted on this record that the life mask was hung on the studio wall, according to photographs, but that it could not be located by 1994. She added that the studio held numerous pictures of Washington as well.

10 Very similar costumes are found in Beginning of the American Union, Reception to Washington on April 21, 1789..., and George Washington (America Must Go Forward).

11 See Podmaniczky, 43, for a photograph of the studio soon after the artist’s death in which can be seen the portrait bust topped by an actual dark, tri-cornered hat. On two easels are the study and the painting in progress of First Farmer of the Land. Another photograph of Wyeth in his studio is taken against the background of Reception to Washington on April 21, 1789...; Podmaniczky, 16.

52 N.

Locations

- (not entered) Iowa State University, Brunnier Main Storage

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1939

Object number: UM83.15

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938

Object number: UM82.120

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938/1939

Object number: UM82.121

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938

Object number: UM83.14

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938

Object number: UM83.16

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938/1939

Object number: UM83.21

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938/1939

Object number: UM83.13

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938/1939

Object number: UM83.18

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938/1939

Object number: UM83.19

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938

Object number: UM83.20

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1939

Object number: UM90.53

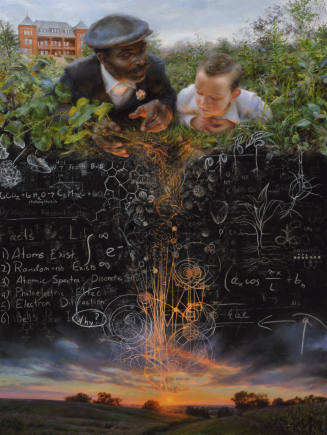

Object Name: Dual Portrait

Rose Frantzen

2015

Object number: U2015.2