America in the Making: Lewis and Clark

Object NamePainting

Artist / Maker

Newell Convers Wyeth

(American, 1882 - 1945)

Date1938

OriginU.S.A.

MediumOil on hardboard (Renaissance panel)

Dimensions26 3/4 × 24 7/8 in. (67.9 × 63.2 cm)

ClassificationsPaintings

Credit LineGift of John Morrell and Company, Ottumwa, Iowa. In the permanent collection, Brunnier Art Museum, University Museums, Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa.

CopyrightUniversity Museums, Iowa State University prohibits the copying or reproduction in any medium of materials on this website with the following exceptions: Iowa State University students, faculty, and staff for educational use in formal instruction, papers, presentations and projects; limited non-commercial; and personal use that meets the criteria for fair use as defined in the U.S. copyright laws.

Images from the University Museums’ collection cannot be used for publication, apparel/non-apparel merchandise, digital or commercial purposes without prior written permission from the University Museums, Iowa State University. Fair use does not apply to the extent that a license agreement or other contract controls reproduction or other use. University Museums and Iowa State University makes no representation that it is the owner of the copyright of the art object depicted in the photo materials and assumes no responsibility for any claims by third parties arising out of use of the photo materials. Users must obtain all other permissions required for usage of the art object and the photo materials.

For more information, please see http://www.museums.iastate.edu/ImageReproduction.html

Object numberUM83.16

Status

Not on viewCollections

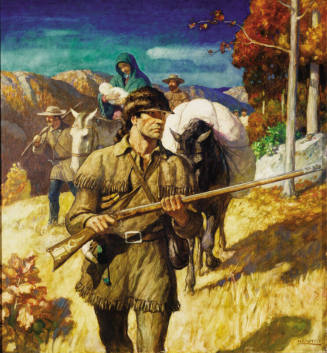

Label TextNo later feat of exploration has exceeded in romantic interest that of the Lewis and Clark expedition (1804-06). Appointed by Thomas Jefferson to explore the Louisiana Purchase, Meriwether Lewis chose William Clark as his companion, traveled 4,000 miles to the Pacific, and collected much valuable scientific data.

The thirteen colonies which had fought for independence from Great Britain were expanding westward, but other countries also claimed rights to the territory beyond the Mississippi. Much of that dispute was resolved in 1803 when Thomas Jefferson, then the third President of the United States, agreed to the Louisiana Purchase. By paying France around $15,000,000 for a vast area of about 800,000 square miles, Jefferson guaranteed American control of the Mississippi River and expanded his country into the regions of the Great Plains and the northern Rocky Mountains. The Purchase also ultimately led to American settlement of the Pacific Northwest, stretching our borders to the Pacific Ocean. Wyeth’s painting shows the first American exploration of this Purchase and captures the spirit of westward expansion.

Aside from political and military issues associated with the newly acquired territory, Jefferson was eager to learn more about the character of the land: its geography and minerals, its plants and animals, and the tribal peoples who inhabited it. He had been interested for years in western exploration and quickly appointed his personal secretary, Meriwether Lewis (1774-1809), to organize an expedition to explore the area and ascertain the best way to cross the continent. Lewis’s choice for a second in command was fellow Virginian, William Clark (1770-1838). Together they outfitted what would become known as the Corps of Discovery. Leaving from St. Louis on May 14, 1804, they traveled up the Missouri River until they stopped at Mandan and Hidatsa villages in October near what is now Bismarck, North Dakota, where they established their winter headquarters. When the expedition resumed its journey the following April of 1805, they were joined by a guide, Toussaint Charbonneau (1767-1843), and his wife Sacagawea (c.1788-1812), a Shoshone woman who had just given birth to her first child February 11.1

Sacagawea spoke both Hidatsa and Shoshone, and she was expected to assist Lewis and Clark to negotiate the purchase of horses from the Indians further west so that the expedition could continue after water navigation was no longer possible. Around the age of twelve, she had been captured from the Lemhi Shoshones by the Hidatsa tribe, from which she was acquired by the French trader, Charbonneau.2 As the explorers continued along the upper reaches of the Missouri and beyond, Sacagawea’s knowledge of the edible plants of the region expanded their diet beyond its main components of deer, elk, bear and other game. The journals of the expedition do not often mention her, but when they do it is usually in favorable terms, such as an early incident in which she saved important cargo when the pirogue which her husband was guiding nearly capsized in the river.3 Clark credited her with saving supplies crucial to the expedition: “the articles which flooded out was nearly all caught by the Squar who was in the rear.”4 They journeyed on, crossing Montana and nearing the Rocky Mountains. Finally, in August of 1805, Sacagawea began to recognize her surroundings, and she reported to Lewis and Clark that they were approaching the land of the Shoshones. Captain Lewis recorded that “the Indian woman recognized the point of a high plain to our right which she informed us was not very distant from the summer retreat of her nation on a river beyond the mountains which runs west. she assures us that we shall either find her people on this river or on the river immediately west of its source; which from its present size cannot be very distant.”5

Sure enough, just over a week later, the expedition encountered Indians who, to Sacagawea’s delight, were her people. According to Clark, the “Squar who [was] before me at some distance danced for the joyful Sight, and she made signs to me that they were her nation.”6 Not only had she returned at last to her own tribe, but a chief among them, Cameahwait, was her brother. Lewis remembered, “Shortly after Capt Clark arrived with the Interpreter Charbono, and the Indian woman, who proved to be a sister of the Chief Cameahwait. the meeting of those people was really affecting.”7 Sacagawea continued on with the expedition, carrying her infant son, Jean-Baptiste, and assisting in negotiations when more horses needed to be purchased. Lewis noted that her presence was a benefit because when other tribal peoples saw her with them, they were assured that the Americans would not threaten them. As he put it in a journal entry of October 13, 1805, “The wife of Shabono our interpetr we find reconsiles all the Indians as to our friendly intentions a woman with a party of men is a token of peace.”8 After an extremely difficult journey, on November 7, 1805, they arrived at last at the western coast where they had to establish a winter camp before starting their return. Lewis and Clark decided that the party should take a vote as to where, exactly, their camp should be and, long before the right to vote was granted to women or Indians, they invited Sacagawea to join in that vote.

The expedition left their winter headquarters, which they had called Ft. Clatsop, on March 23, 1806, and headed back toward the east. In July, Sacagawea recommended a route through what is known now as Bozeman Pass in southern Montana, as Clark recorded. “the Indian woman wife to Shabono informed me that she had been in this plain frequently and knew it well...and when we assended the higher part of the plain we would discover a gap in the mountains....The Squar pointed to the gap through which she said we must pass.”9 The explorers arrived back at the Mandan villages in August, and Lewis and Clark invited Sacagawea and her family to continue on with them to St. Louis, but they declined. From there, the journey was fast and easy, compared to the trials they had endured as they crossed the continent, and the Corps of Discovery appeared in St. Louis on September 23, 1806. They had been gone two years and four months and had been presumed dead by many. They were met, remembered Clark, “by all the village and received a harty welcom from it’s inhabitants.”10 According to another of the explorers, “the party all considerable much rejoiced that we have the Expedition Completed.”11 Lewis and Clark soon went to Washington for a personal report to President Jefferson, who gave both of them grants of land. In addition, Lewis was named governor of the new Louisiana Territory and Clark became the Indian agent for the West. A few years later, in 1810, Charbonneau brought his family to Missouri where Clark offered to help him establish a farm. After only three months, however, Charbonneau returned to the West, taking Sacagawea with him, but leaving behind their son, Jean-Baptiste. All of the Corps of Discovery had grown fond of the child during their journey, Clark in particular, and he took the young boy into his family.

We do not know for certain what scene from this journey of over seven thousand miles Wyeth illustrated or if he intended to illustrate a particular incident at all. He may have been simply trying to capture a sense of the western wilderness and the courage of the first American expedition to explore it. The scene may be in August, 1805, depicting Lewis at the top of the continental divide where, as Sacagawea points toward the land of her people, he sees more mountains to cross instead of rivers flowing immediately westward. If we take a different orientation, it might also be on the return journey when Sacagawea pointed out the Bozeman Pass.12 The idea of the journey back to the East, however, would generally not be regarded as possessing nearly so much of the “romantic interest” which the caption attributes to the adventure. Whichever the case, and despite the fact that the calendar caption does not mention her at all, Wyeth clearly depicts Sacagawea as an active guide for the expedition and not just the Shoshone interpreter. The two men in the picture are probably intended to be Lewis and Clark, but the figure in back, dressed in a frontier buckskin outfit, could be Charbonneau instead. Sacagawea was rarely studied before the early twentieth century and few images of her are to be found.13 Among the earliest is a 1905 bronze sculpture by Alice Cooper (1875-1937) in which, while holding her child, she lifts her right arm and extends it fully, pointing as in the Wyeth painting. A 1914 sculpture by Cyrus Dallin imagined her similarly, as does a 1917 watercolor by Charles M. Russell.14 By the time of Wyeth’s painting, the depiction of Sacagawea as a figure pointing into the distance “had become something of a cliché.”15 Most images of Sacagawea portray her as a young, attractive woman and some as the teenager (around 16 or 17) she actually was when she journeyed with the Corps of Discovery. In Wyeth’s portrait however, she appears as a very serious and not especially young woman.

The costumes worn by the figures in Lewis and Clark are typical of those worn in other western scenes by Wyeth. Sacagawea’s clothing is a buckskin dress with a geometric design that was probably made of porcupine quills. Her leggings and moccasins also are decorated; she wears a thin headband and an ear decoration, and carries a red blanket over her arm. Wyeth’s tax records note costs for costumes and travel to both Wilmington and Philadelphia, probably for research at libraries and museum collections, and to New York. He may have consulted the collections of George Heye’s Museum of the American Indian which had opened there in 1916 or those of the Museum of Natural History, which also had Native American collections. The men’s costumes are similar to those painted in Jacques Marquette, Daniel Boone, and Sam Houston. The rifle, like that depicted in Daniel Boone, appears to be modeled after one that hung over the mantel in Wyeth’s studio. His Western subjects were especially well regarded, perhaps partly because they reflected direct experience. Wyeth was not widely traveled, but as a young man, he did journey to the West to satisfy his lifelong curiosity. In 1904, he spent a few months in Colorado and New Mexico and then returned briefly to Colorado in 1906. Oddly, considering how frequently he took on western subjects, this calendar scene is the only one of his career specifically about the Lewis and Clark expedition.

Like several of the pictures in America in the Making, Lewis and Clark has a strong leftward orientation. In this case, as in his Covered Wagons for October, the tendency is to read the composition as a reference to the West. When he positioned Sacagawea far to the left side then had her extending her arm so close to the left edge, the clear implication was that the viewer should imagine the western space well beyond this scene. The other two figures follow her pointing hand and gaze fixedly in that direction. The landscape in the background is by far the most rugged in the twelve calendar paintings and is surely meant to suggest the remoteness and the difficulty of the terrain. Wyeth positions his character on a promontory where, like them, we can see miles into the distance.

ENDNOTES

1 The dates of both Charbonneau and Sacagawea have been a matter of dispute, but those cited are the most commonly given. In 1933, Grace R. Hebard, a Wyoming historian, published Sacajawea: A Guide and Interpreter of the Lewis and Clark Expedition in which she claimed that Sacagawea had in fact left Charbonneau and gone back to her own tribe, the Shoshone, and lived into old age. Hebard’s assertions in this regard are now not regarded as credible. Evidence suggests that she died in South Dakota in 1812 at the age of 25. A second child, Lizette, was born in 1812, but she apparently died in childhood.

2 Sacagawea was the second wife of Charbonneau, and it is not known for certain what the circumstances of the relationship were. It is also not clear why his other wife stayed behind at Ft. Mandan and Sacagawea joined the expedition though she had so recently given birth; perhaps it was due to her knowledge of the Shoshone language and territory. In the journals of the Corps of Discovery, she is sometimes referred to as Charbonneau’s wife, his woman, his squaw (sometimes spelled “squar”), the Indian woman, and sometimes by her name. Her name has also never been precisely determined, and when it is mentioned in Lewis’s and Clark’s journals, they often spelled it out phonetically, but with no consistency. When the vote was taken at Ft. Clatsop as to where the group should make winter camp, she was called “Janey.”

3 Lewis and Clark were the primary journalists, but others, notably Charles Floyd, John Ordway, and Joseph Whitehouse also recorded the journey. The standard and most authoritative source for all journals is that edited by Gary E. Moulton and a team from the University of Nebraska’s Center for Great Plains Studies, published in 2002. An extensive website provides all the journal entries as well as an abundance of other information about the Lewis and Clark expedition. All journal quotations here are from that website, cited as Nebraska Journals. http://lewisandclarkjournals.unl.edu/.

4 Clark, May 14, 1805. Nebraska Journals. The spelling, grammar, and other characteristics of the journals are quoted without change.

5 Lewis, August 8, 1805. Nebraska Journals.

6 Clark, August 17, 1805. Nebraska Journals.

7 Lewis, August 17, 1805. Nebraska Journals.

8 Lewis, October 13, 1805. Nebraska Journals.

9 Clark, July 6, 1806. Nebraska Journals.

10 Clark, September 23, 1806. Nebraska Journals.

11 Ordway, September 23, 1806. Nebraska Journals.

12 When the caption for this painting mentions “4,000 miles to the Pacific,” it might suggest that this scene is on the journey west and not the return.

13 For a history of the imagery of Sacagawea, see the series of four articles on the website of the Chief Washakie Foundation by Brian W. Dippie, “Sacagawea Imagery.” http://www.windriverhistory.org/exhibits/sacajawea/sac01.htm.

14 The Cooper sculpture is in Washington Park in Portland, Oregon. Dippie, part 1. Dallin (1890-1966) taught art at Arlington, Massachusetts, and it is nearly certain that Wyeth would have been well acquainted with his sculpture. For a brief discussion of Dallin and other sculptors’ depictions of Sacagawea, see Dippie, part 3. The watercolor by Russell (1864-1926) is reproduced and discussed in Dippie, part 2.

15 Dippie, part 3.

Locations

- (not entered) Iowa State University, Brunnier Main Storage

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1939

Object number: UM90.53

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1939

Object number: UM83.15

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938

Object number: UM83.14

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938

Object number: UM82.120

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938/1939

Object number: UM82.121

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938/1939

Object number: UM83.17

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938

Object number: UM83.20

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938/1939

Object number: UM83.21

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938/1939

Object number: UM83.19

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938/1939

Object number: UM83.13

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938/1939

Object number: UM83.18