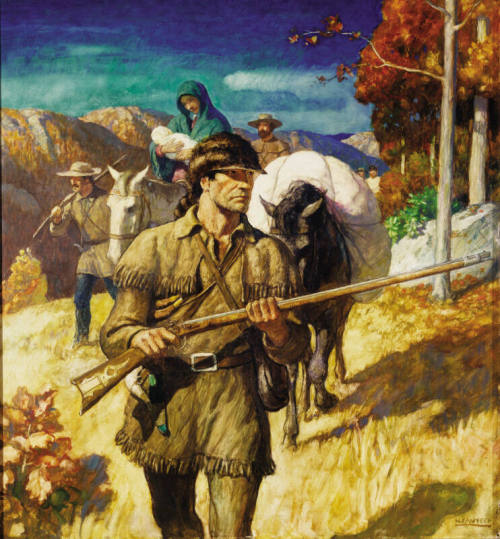

America in the Making: Daniel Boone

Object NamePainting

Artist / Maker

Newell Convers Wyeth

(American, 1882 - 1945)

Date1939

OriginUSA

MediumOil on hardboard (Renaissance Panel)

Dimensions26 3/4 × 24 7/8 in. (67.9 × 63.2 cm)

ClassificationsPaintings

Credit LineGift of John Morrell and Company, Ottumwa, Iowa. In the permanent collection, Brunnier Art Museum, University Museums, Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa.

CopyrightUniversity Museums, Iowa State University prohibits the copying or reproduction in any medium of materials on this website with the following exceptions: Iowa State University students, faculty, and staff for educational use in formal instruction, papers, presentations and projects; limited non-commercial; and personal use that meets the criteria for fair use as defined in the U.S. copyright laws.

Images from the University Museums’ collection cannot be used for publication, apparel/non-apparel merchandise, digital or commercial purposes without prior written permission from the University Museums, Iowa State University. Fair use does not apply to the extent that a license agreement or other contract controls reproduction or other use. University Museums and Iowa State University makes no representation that it is the owner of the copyright of the art object depicted in the photo materials and assumes no responsibility for any claims by third parties arising out of use of the photo materials. Users must obtain all other permissions required for usage of the art object and the photo materials.

For more information, please see http://www.museums.iastate.edu/ImageReproduction.html

Object numberUM90.53

Status

Not on viewCollections

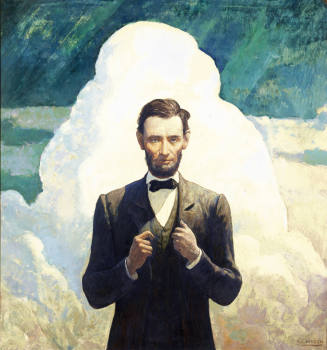

Label TextOne of the most picturesque of American pioneers, Boone was a great hunter and trapper, skilled in woodcraft, a famous guide and Indian fighter, resourceful and fearless. In 1775, he led into Kentucky a party of settlers who founded Boonesborough. They are shown going into this fertile territory through Cumberland Gap.

As the caption for the May calendar illustration describes, Daniel Boone (1734-1820) was the quintessential American frontiersman, a legendary figure in the making of America. During his own lifetime, his exploits were renowned and by the time of his death in 1820, he had become a symbol of America’s westward march. The caption’s characterization of Boone as an “Indian fighter, resourceful and fearless” was given sculptural form as early as 1826 in The Conflict Between Daniel Boone and the Indians, a relief for the rotunda of the United States Capitol.1 He was likely the inspiration for the hero of James Fenimore Cooper’s 19th century series of novels, the Leatherstocking Tales, about the settling of America (including The Last of the Mohicans). In the 20th century, he was a common character in American films and television, always depicted as a courageous, pioneering trailblazer wise in the ways of the wilderness. In fact, Boone did carve out a trail, known as the Wilderness Road, by which settlers could cross the Appalachian Mountains and move west. For his role in the opening up of this territory, he was sometimes called the Columbus of the Woods.

Boone was born in Pennsylvania to a Quaker family who moved to North Carolina in 1750. He began as a hunter and trapper at a time when the woods teemed with wildlife, including buffalo, which at that time still ranged well east of the Mississippi. The animals were hunted largely for their skins, though they were also an important food source. Boone was accustomed to spending long periods of time alone in the forest, hunting and trapping in uncharted territory, and his travels took him (sometimes as a captive) from Florida to Michigan. He fought many battles and skirmishes with Indians (two of his sons and others of his extended family were killed and one of his daughters was kidnapped until Boone rescued her), but his relations with them were often cordial. He was adopted into the Shawnee tribe, and he expressed his admiration for Indians and their way of life.

Wyeth depicts Boone in one of his most famous adventures: leading a band of settlers, including his own family, through the Cumberland Gap into Kentucky (which is spelled variously in early documents). The Appalachian Mountains, a range that runs along the eastern part of the United States from Maine into Georgia, were an obstacle to large-scale settlement until around the time of the Revolutionary War. The Cumberland Gap, near the juncture of the present states of Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia, was a route through those mountains that was first an animal trail and then used by tribal groups. Boone first saw the Gap in 1769, and his description of the mountains was recorded near the end of his life. “These mountains are in the wilderness, as we pass from the old settlements in Virginia into Kentucke,...are of a great length and breadth, and not far distant from each other. Over these, nature hath formed passes, that are less difficult than might be expected from a view of such huge piles. The aspect of these cliffs is so wild and horrid that it is impossible to behold them without terror.”2

However fearsome these mountains seemed, Boone continued his moves into the territory, despite the fact that the British Proclamation of 1763 banned settlement west of the Appalachians and treaties with the Indian tribes were in place. He later recalled, “I returned home to my family with a determination to bring them as soon as possible to live in Kentucke, which I esteemed a second paradise, at the risk of my life and fortune.”3 He did indeed assume risk in 1773 when he gathered his and five other families and headed toward Kentucky. After his party was attacked by Indians, and one of his sons captured and tortured to death, all turned back and abandoned their plan. In 1775, the Transylvania Company negotiated the Treaty of Watauga with the Cherokee to purchase a large area in Kentucky. They then hired Boone to establish the Wilderness Road through the Cumberland Gap so that settlers could move into Kentucky. The first large party to use the trail was Boone’s own, with which he founded Boonesborough in 1775, and he proclaimed that his wife and daughter were “the first white women that ever stood on the banks of the Kentucke river.”4

Crossing the Cumberland Gap under the watchful eye of Boone is the subject of Wyeth’s painting. Boone is in full frontiersman costume5, wearing a buckskin shirt6, as he leads the settlers across a meadow with the mountains in the background. He looks to his left, gun at the ready, as if prepared to repulse an attack from the surrounding forest. Though it is nearly certain he would not have worn a coonskin cap7, the rifle is similar to those used at the time and is based on an antique weapon in Wyeth’s personal collection of accessories for his history paintings.8 Boone’s features are known through a portrait painted in the last year of his life by Chester Harding (1792-1865). Harding sketched and painted Boone in 1820 when the elderly frontiersman was living at the home of his daughter in Missouri. Aside from the straight, prominent nose and the downturned mouth, however, Wyeth seems to have idealized Boone.9

Seated on a horse behind him is a female figure with a swaddled infant in her arms, usually interpreted as Boone’s wife, Rebecca Bryan Boone (1738-1813). The mother of ten children, her presence in such paintings is often intended to symbolize the pioneer women who endured many difficulties as they participated in the westward drive. Wyeth may be intending to show her in 1773 when she gave birth to her son, Jesse Bryan; in 1775, however, a son born that year had died before the trip to Kentucky. The presence of an infant and Rebecca’s costume of a blue cloak that also covers her head associates her with traditional images of the Madonna and, in this case, “The Flight into Egypt,” in which Mary holds the child Jesus in her arms as she rides a donkey led by her husband, Joseph. Wyeth would have certainly known the famous painting of 1851-52 by George Caleb Bingham depicting Boone’s passage through the Cumberland Gap.10 In that painting, Boone physically leads his wife’s horse through a dark and forbidding landscape that seems perfect for hiding terror and dangers. Wyeth’s painting, however, is far less dramatic in the depiction of the landscape and focuses on Boone himself rather than the passage of the group as a whole. Wyeth does, however, adopt the orientation of Bingham’s painting that depicts the solemn group of settlers stepping forward from the dark background toward the viewer. In several others in his calendar series, Wyeth composed his paintings so that a westward movement is implied. Daniel Boone, in contrast, strides directly outward, so close to the foreground of the picture that his figure is cut off at the knees. The immediacy of this compositional device concentrates attention on the alert and heroic figure of Daniel Boone.11

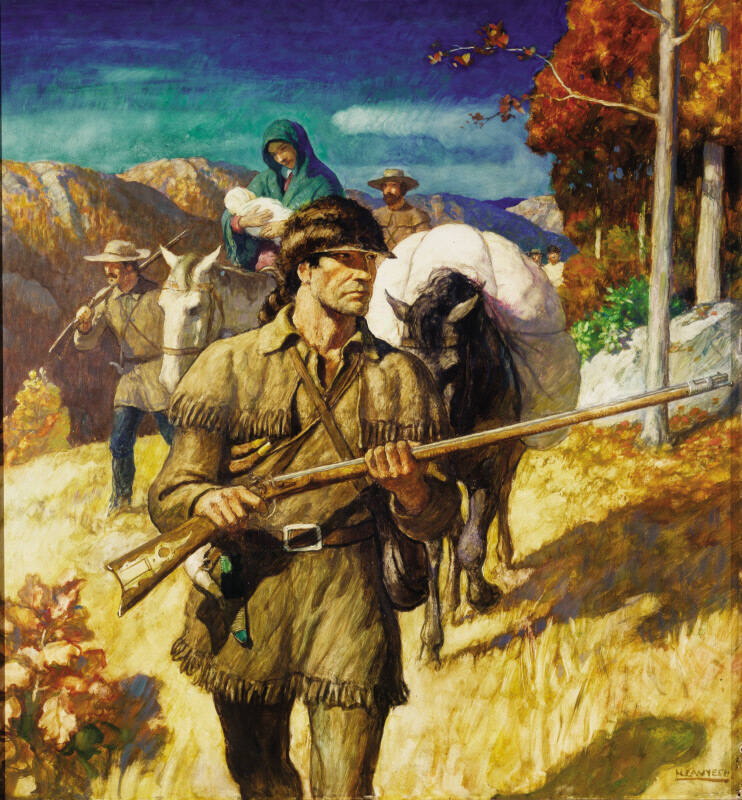

Wyeth contributed an illustration for a 1938 calendar which was similar to his 1940 image of Daniel Boone at Cumberland Gap, except that now the orientation of the painting is more horizontal, showing the party clearly moving from east to west. Entitled Dan’l Boone –The Home Seeker –Cumberland Valley, the oil painting contains much the same cast of characters: Boone in the lead, a mother and child on a horse, and several other frontiersmen and settlers. In both paintings, the landscape is suffused with light and evokes a tone of hopefulness and adventure. The landscape is not portrayed as a “howling wilderness,” a term used by Boone and others to describe these lands before these “home-seekers” established their settlements. This work and the 1940 calendar page have a stronger suggestion of Boone’s pronouncement about the success of all his endeavors: “Thus we behold Kentucke, lately an howling wilderness, the habitiation [sic] of savages and wild beasts, become a fruitful field.”12

ENDNOTES

1 Wearing his fringed frontier buckskin and holding a rifle similar to that in Wyeth’s painting, Boone is shown locked in hand-to-hand combat with a tomahawk-wielding Indian, while a second Indian lies dead at his feet. This sandstone relief is by Enrico Causici (1790-1835), an Italian artist who produced several other works of art for the building. Boone and the warrior look each other directly in the face, and their confrontation is meant to be seen as a life or death struggle. Boone’s features have some resemblance to his portraits while the profiled face of the Indian is a hideous, sharply-carved mask. The date of the carving, 1826-27, suggests that the artist was giving form to the attitudes behind the wars against and the forced removal of tribal peoples.

2 This description was written by John Filson, who recorded Boone’s reminiscences during Boone’s lifetime, when he was an old man living in Missouri. Though it is generally regarded as a fanciful account, colored by Filson’s elaborate prose, Boone vouched for its accuracy. Boone’s story appeared as an appendix to Filson’s larger history of Kentucky. Filson, John, “The Adventures of Col. Daniel Boon[sic],” appendix in The Discovery, Settlement and Present State of Kentucke, Wilmington, Delaware: John Adams, 1784; also available online at http://gutenberg.org/etext/909. Boone himself did dictate an autobiography, but it was lost when a canoe capsized (the same way that Joliet’s record of his Mississippi voyage was lost). Kentucky is spelled variously in documents on Boone and the state’s early history. Contrary to some references to him, Boone was not at all illiterate. Supposedly his two favorite books were the Bible and Gulliver’s Travels by Jonathan Swift; in fact, he carried Swift’s book with him on his travels and read it to his companions when they camped for the night. Brown, Meredith Mason, Frontiersman: Daniel Boone and the Making of America, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2008, 2, 49.

3 Filson.

4 Filson.

5 Though perhaps not exactly what Boone would have worn as he traversed the woods and mountains, Wyeth’s depiction is reasonably accurate. It is certainly typical of the way he had been depicted in American art of the 19th century. A recent biographer of Boone’s described his appearance: “Boone looked like, and was, a backwoodsman. Like other hunters on the frontier, he wore deerskin moccasins reaching up his calves and a long hunting shirt of linsey or of deerskin reaching down to his knees. Often, instead of pants, he would wear a breechclout and deerskin leggings attached to a belt. His clothes looked a lot like an Indian’s -- because they were a lot like an Indian’s. They were clothes well designed for moving through the woods and for camouflage. He wore a hat, often one made of beaver fur. According to his son, Nathan, Boone “’always despised the raccoon fur caps and did not wear one himself.’” Brown, 22. Boone’s son’s comments are found in My Father, Daniel Boone: The Draper Interviews with Nathan Boone, ed. by Neal O. Hammon, Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 1999, 36-37, and 293, n.9.

6 According to Wyeth’s accounts for tax purposes, he rented a costume, which he specifies as “buckskin,” for $50.00, an unusually large amount for costume rental. The author thanks Christine Podmaniczky for her very helpful comments in regard to this painting.

7 See the comment of Boone’s son in n.5.

8 Podmaniczky, 40, fig.16a. The gun is similar to that depicted in Lewis and Clark and Sam Houston. The Iowa State painting of Daniel Boone has been used as an illustration for Glass, Herb, “The Long, Long Rifle,” The American Gun, vol. I, no.2, Spring 1961, 42.

9 Harding’s portrait and many other images of him can be seen in Sweeney, J. Gray, The Columbus of the Woods: Daniel Boone and the Typology of Manifest Destiny, St. Louis: Washington University Art Gallery, 1992, color plate 1.

10 For a thorough discussion of this subject, see Sweeney’s chapter VI, “An American Moses: George Caleb Bingham’s Daniel Boone Escorting Settlers Through the Cumberland Gap,” 40-51.

11 This painting has itself had some adventures. In 1969 the painting was stolen. Its location was unknown for many years until it was discovered in the collection of the Brandywine River Museum which graciously restored it to the University Museums.

12 Filson.

Locations

- (not entered) Iowa State University, Brunnier Main Storage

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938

Object number: UM83.16

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1939

Object number: UM83.15

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938/1939

Object number: UM83.18

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938/1939

Object number: UM83.21

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938

Object number: UM83.14

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938

Object number: UM83.20

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938/1939

Object number: UM83.19

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938/1939

Object number: UM83.13

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938/1939

Object number: UM83.17

Object Name: Mural (three panels)

Grant Wood

1936-1937

Object number: U88.68abc