America in the Making: Jacques Marquette

Object NamePainting

Artist / Maker

Newell Convers Wyeth

(American, 1882 - 1945)

Date1938/1939

MediumOil on hardboard ( Renaissance Panel)

Dimensions27 x 25 in. (68.6 x 63.5 cm)

ClassificationsPaintings

Credit LineGift of John Morrell and Company, Ottumwa, Iowa. In the permanent collection, Brunnier Art Museum, University Museums, Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa.

CopyrightUniversity Museums, Iowa State University prohibits the copying or reproduction in any medium of materials on this website with the following exceptions: Iowa State University students, faculty, and staff for educational use in formal instruction, papers, presentations and projects; limited non-commercial; and personal use that meets the criteria for fair use as defined in the U.S. copyright laws.

Images from the University Museums’ collection cannot be used for publication, apparel/non-apparel merchandise, digital or commercial purposes without prior written permission from the University Museums, Iowa State University. Fair use does not apply to the extent that a license agreement or other contract controls reproduction or other use. University Museums and Iowa State University makes no representation that it is the owner of the copyright of the art object depicted in the photo materials and assumes no responsibility for any claims by third parties arising out of use of the photo materials. Users must obtain all other permissions required for usage of the art object and the photo materials.

For more information, please see http://www.museums.iastate.edu/ImageReproduction.html

Object numberUM82.121

Status

Not on viewCollections

Label TextPere Marquette, French Jesuit Missionary, with Louis Joliet, a trader, explored the Mississippi River from the Wisconsin to its confluence with the Arkansas. The scene shows their entrance upon the broad, calm bosum [sic] of the Father of Waters, May 17,

1673, the great stream disappearing into the distance.

Marquette and Joliet were French explorers whose journeys on the upper Mississippi River in 1673 determined that the great river emptied into the Gulf of Mexico rather than the Pacific Ocean. Early French settlers in the Great Lakes region had learned from native tribes that a large river lay to the west, and the Europeans hoped that it extended as far as the Pacific Ocean, providing a coast-to-coast system of water transportation.1

Jacques Marquette (1637-1675) arrived in Quebec in what was known as New France

in 1666 to join the effort to convert the Indian tribes in the Great Lakes region. Born at Laon, France, he was ordained into the Jesuits (also known as the Society of Jesus), an order whose primary goal was the spreading of Christianity, especially into those areas of the world which were being discovered and explored in the 16th and 17th centuries. Often called “Black Robes” by the tribes to whom they preached the Gospel, these missionaries were willing to accept any hardship, including martyrdom, to bring their message to the native peoples. Pere Marquette’s first concern, at this time, was not

exploration, but evangelization.

Louis Joliet (1645-1700) was born in Quebec and grew up in New France, where he was

acquainted with the tribes of the area and their languages. He spent a period of his youth in a Jesuit seminary but abandoned the religious life to become a mapmaker and trader. Described by Father Marquette as having “the Courage to dread nothing where everything is to be Feared,”2 Joliet also made maps and kept a record of the journey. All of these were lost when his canoe overturned later in the St. Lawrence River, leaving Marquette’s report as the primary source of information.

Marquette and Joliet led a small expedition in two birch bark canoes across the northern

edge of Lake Michigan until they entered the Fox River around Green Bay, Wisconsin. After paddling up the Fox, two guides from the Miami tribe (who, according to Marquette, “could not sufficiently express their astonishment at the sight of seven frenchmen, alone and in two canoes, daring to undertake so extraordinary and so hazardous an Expedition”) assisted them in the portage across to the Wisconsin River, a tributary of the Mississippi.3 Following the Wisconsin, Marquette and his companions “safely entered Missisipi [sic] on The 17th of June, with a joy that I cannot Express.”4 The date of May 17th given in the caption for the painting is actually the date on which the expedition had begun.Subsequent entries in Marquette’s journal record what they saw on the journey down the river, such as “monstrous fish,” buffalo (which he called “wild cattle”) in herds as large as four hundred, new plants and fruits, a huge painting of mythical creatures on rocks above the water (“which at first made Us afraid”)5, and the tribes they encountered. These peoples, of course, were Marquette’s main interest since he hoped to convert them to Christianity. He spoke several tribal languages and was generally able to communicate with the native peoples. The French explorers’ first contact on their trip was with the Illinois who, Marquette noted, “probably recognized us as frenchmen, especially when they saw a black gown.”6 They were welcomed into the village, were guests at a feast (where they were fed their food by an Illinois who, Marquette wrote, placed it into

a spoon “and put it to my mouth As if I were a little Child,”)7 and then given a calumet, or a tobacco pipe. The explorers could not carry all the gifts they were offered; however they did retain the calumet, since it could be (and would be) used in making peace with other tribes further down the river.

They explored the Mississippi as far south as the point at which the Arkansas River flows into it. A tribe Marquette called the “Akamsea” welcomed the travelers and listened while the Jesuit told them “about God and the mysteries of our holy faith. They manifested a great desire to retain me among them, that I might Instruct them.”8 The Indians told Marquette and Joliet that they were only about ten days from the sea, but they also informed the French that the tribes further south were hostile and that they would likely fall “into the hands of the Spaniards who, without doubt, would at least have detained [them] as captives.”9 Fearing that either of these two fates would “expose [them] to the risk of losing the results of this voyage” and believing that they had “obtained all the information that could be desired in regard to this discovery,”10 they decided to return north. By then, it was clear to the explorers that, “beyond a doubt, the Missisipi [sic] river discharges into the florida or Mexican gulf, and not to The east in Virginia...or to The west in California.”11 Ascending back up the Mississippi in July of 1673, they came to Kaskas[k]ia, a village of the Illinois who escorted them to the Illinois River, which was a shorter route back to Lake Michigan. Pere Marquette stayed at the mission of Saint-Francois-Xavier to continue

his missionary work while Joliet set off to the east, back toward Quebec. The following year, Marquette returned to the Illinois to resume his conversion of the tribe, but his health began to fail. In May of 1675, Pere Marquette died on his way back to his home mission and was buried on the shore of Lake Michigan.12

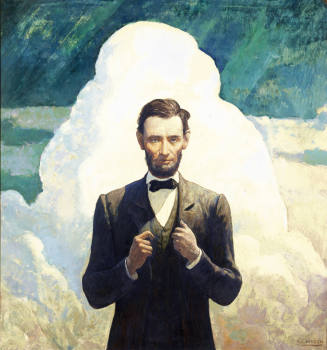

As the caption for the March painting states, Wyeth depicts the French explorers entering the waters of the Mississippi River. The Jesuit priest, standing up in the canoe with the crucifix prominently displayed in his hand, dominates the composition. Perhaps the reference in the caption to the Mississippi as the “Father of Waters” is intended to draw a comparison with the importance of Father Marquette and his pioneering efforts toward conversion. His journal describes how carefully they scanned the shores marveling at the new environment and looking for any sign of Indians. The sense of alert observation conveyed by every figure in the canoes expresses both the trepidation and

determination of the explorers, as described by Marquette. Pere Marquette is the only figure who can be securely identified in Wyeth’s painting, though it is likely that Joliet is either the figure sitting just in front of the priest or the man holding an upright paddle in the front of the second canoe. Both men are dressed in a frontier fashion, appropriate for the adventurous Joliet. Portraits of Marquette exist, but none are known for Joliet. In subsequent images, however (such as the sculpture at the library for the city of Joliet, Illinois), he is often shown with a broad-brimmed hat. The man who holds the paddle echoes the strong vertical of Marquette’s figure in the composition, so it is possible that

Wyeth intended to draw attention to that figure as representing Joliet. In several of Wyeth’s paintings for America in the Making, the landscape is as important as the human figures in the composition and in the narrative. The immensity of the American continent and its distance from European society, along with the daunting prospect of trying to push into that wilderness is suggested by Wyeth’s composition. It seems likely that the painter was familiar with George Caleb Bingham’s iconic image of the American West, Fur Traders Descending the Missouri of 1845 (it entered the collection of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1933) in which two frontier figures float on a quiet river in a canoe. Marquette and Joliet had passed by the confluence of the Missouri River with the Mississippi, but had declined to paddle westward to trace its path out onto the Plains. In both paintings, the tone of solitude and isolation in a wilderness that nearly overwhelms the human beings is balanced by the beauty and mystery of the land. In both the Wyeth and the Bingham paintings, the progress along the smoothly flowing river is slow and nearly stilled, the surface displaying scarcely a ripple and reflecting the travelers and the sky above them. The large expanse of sky might leave the impression that Wyeth’s

horizon line is very low in this painting. But in fact the composition is divided almost exactly in half, with the cloud-reflecting water taking up about half the space. The white cumulus clouds puff from overhead to the horizon, while the center is suffused with a bright, radiating light. The strong light of the background throws the figures, Father Marquette in particular, into a dramatic silhouette, which is further emphasized by the viewpoint; we look slightly upward as the explorers look penetratingly around them. Standing erect in the canoe in his full-length black robe and holding the crucifix as if it is both an announcement and a protection, Jacques Marquette embodies the spiritual zeal that animated the Jesuit missionaries to the New World.

These pictorial devices may suggest a certain sympathy on Wyeth’s part for the “Black Robes” as well as the fortitude of Joliet and others who ventured into the American willderness. In his long career, Wyeth painted no other pictures of this incident from American history and, in fact, the title refers only to Marquette and not Joliet at all. It is not known if Wyeth himself determined the subjects for America in the Making or if they originated with John Morrell and Company, so it is not clear if this picture represents the artist’s personal choice. In any case, the focus on Marquette and the heroicism with which he is depicted here gives significance to the role religious figures played in exploring and settling the United States.13 Wyeth’s interpretation of this part of American history seems to imply not only this voyage of discovery, but also the introduction of Christianity to the tribes along the river as positive developments, an attitude that would have been common among Americans of Wyeth’s background at that time. It is also

possible that Wyeth was attempting to bring some geographical balance to his series by

including an incident from the Great Lakes and the Midwestern regions.

In contrast to the other paintings for America in the Making, the Wyeth archives contain

no account of the expenditures involved in producing the picture.

ENDNOTES

1 Marquette, Jacques, “Voyages du P. Jacques Marquette,” Travels and Explorations of the Jesuit Missionaries in New France, 1610-1791, The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents, vol. LIX, edited by Reuben Gold Thwaites, Cleveland: The Burrows Brothers Co., 1900; republished by University Microfilms, Ann Arbor, Mich., 1966 (March of America

Facsimile Series, vol. 28); 87. Both the original French and an English translation which maintains Pere Marquette’s spellings of proper names and his capitalization are included in this edition. It also contains reproductions of the maps drawn by Father Marquette. The original papers are at St. Mary’s College in Montreal. Marquette records that their assignment was to “seek a passage from here to the sea of China, by the river that discharges into the Vermillion, or California Sea.” They were also to determine if there was any truth to rumors of “Quiuira [sic]...in which numerous gold mines are reported

to exist.” (87). Like Coronado, Marquette and Joliet March Jacques Marquette learned that this golden city was a myth. Joliet is sometimes spelled Jolliet; in his journal, Marquette

spells it Jolyet or Jollyet. Marquette’s journal can be accessed on the website of the Wisconsin Historical Society: http://www.wisconsinhistory.org/turningpoints/search.asp?id=370.

2 Marquette, 89.

3 Marquette, 105. Marquette calls the Wisconsin River the “Meskousing.”(107). In earlier travels along the shore of Lake Michigan, Marquette told what he called the tribe of the “folle avoine” his plans for further exploration, plans which they cautioned against because, they said, the Europeans would “meet Nations who never show mercy to Strangers, but Break Their heads without any cause.”(95) As for the object of the expedition, “they also said that the great River was very dangerous...that it was

full of horrible monsters, which devoured men and Canoes Together; that there was even a demon, who...barred the way and swallowed up all who ventured to approach him; Finally that the Heat was so excessive In those countries that it would Inevitably Cause

Our death. I thanked them for the good advice that they gave me, but told them that I could not follow it, because the salvation of souls was at stake, for which I would be delighted to give my life.”(97)

4 Marquette, 107.

5 Marquette, 139-140. “While skirting some rocks, which by Their height and Length inspired awe, We saw upon one of them two painted monsters which at first made Us afraid, and upon Which the boldest savages dare not Long rest their eyes. They are as

large As a calf; they have Horns on their heads Like those of deer, a horrible look, red eyes, a beard Like a tiger’s, a face somewhat like a man’s, a body Covered with scales, and so Long A tail that it winds all around the Body, passing above the head and going back between the legs, ending in a Fish’s tail. Green, red, and black are the three Colors composing the Picture. Moreover, these 2 monsters are so well painted that we cannot believe that any savage is their author; for good painters in france would find it difficult to paint so well, -- and besides, they are so high up on the rock that it is difficult to reach that place Conveniently to paint them.” Marquette’s word for the peoples he encountered is “sauuages” (sauvages), or savages, a term commonly used by Europeans in that period.

6 Marquette, 115.

7 Marquette, 123.

8 Marquette, 155.

9 Marquette, 159.

10 Marquette, 160-161.

11 Marquette, 159.

12 An account of his last mission to the Indians and his death is found in “Recit du second voyage et de la mort du P. Jacques Marquette,” (Account of the second voyage and the death of Father Jacques Marquette), Travels and Explorations of the Jesuit

Missionaries, 184-211.

13 Today, the European quest for conversion of native populations to Christianity would not be seen in so positive a manner. Wyeth seems to take at face value Marquette’s belief that his explorations had the primary goal of “saving souls,” whereas contemporary commentators might be more likely to lament the disease, exploitation, cultural destruction, geographical displacement, and at times even the annihilation of these tribal groups. In his writings on his Mississippi voyage and his other missions, Marquette often indicated that he felt welcomed among the tribes and that they listened patiently to his

explanations of the Christian faith.

Locations

- (not entered) Iowa State University, Brunnier Main Storage

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938

Object number: UM82.120

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938/1939

Object number: UM83.17

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1939

Object number: UM83.15

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938/1939

Object number: UM83.13

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938

Object number: UM83.14

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938

Object number: UM83.16

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938/1939

Object number: UM83.18

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938/1939

Object number: UM83.19

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938/1939

Object number: UM83.21

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938

Object number: UM83.20

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1939

Object number: UM90.53