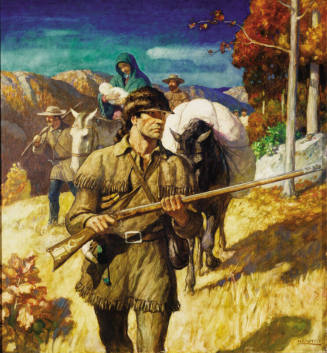

America in the Making: Covered Wagons

Object NamePainting

Artist / Maker

Newell Convers Wyeth

(American, 1882 - 1945)

Date1939

OriginUnited States

MediumOil on hardboard (Renaissance panel)

Dimensions26 3/4 x 24 7/8 in. (68.6 x 63.5 cm)

ClassificationsPaintings

Credit LineGift of John Morrell and Company, Ottumwa, Iowa. In the permanent collection, Brunnier Art Museum, University Museums, Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa.

CopyrightUniversity Museums, Iowa State University prohibits the copying or reproduction in any medium of materials on this website with the following exceptions: Iowa State University students, faculty, and staff for educational use in formal instruction, papers, presentations and projects; limited non-commercial; and personal use that meets the criteria for fair use as defined in the U.S. copyright laws.

Images from the University Museums’ collection cannot be used for publication, apparel/non-apparel merchandise, digital or commercial purposes without prior written permission from the University Museums, Iowa State University. Fair use does not apply to the extent that a license agreement or other contract controls reproduction or other use. University Museums and Iowa State University makes no representation that it is the owner of the copyright of the art object depicted in the photo materials and assumes no responsibility for any claims by third parties arising out of use of the photo materials. Users must obtain all other permissions required for usage of the art object and the photo materials.

For more information, please see http://www.museums.iastate.edu/ImageReproduction.html

Object numberUM83.15

Status

Not on viewCollections

Label TextA dramatic era in the making of America was the covered wagon trek to the West. In 1831, Nathaniel Wyeth, ancestor of the artist, led an expedition into Oregon. In this painting Mr. Wyeth has caught the sense of the vast spaces and great skies, with the slow-moving wagon train crawling through an endless sea of grass.

The caption for Covered Wagons speaks of the dramatic era of the great westward migrations, but it was “dramatic” only in retrospect. For those pioneers who crossed the Great Plains, the trip was noted for its monotony as day after day, they trudged through a featureless and desolate land. It was a long, hot, dry, dangerous, and dusty trek along grasslands that seemed to go on forever under an enormous sky. Even Horace Greeley (1811-1872), who had famously advised, “Go West, young man, and grow up with the country,” recognized that following his advice involved hardship. In 1869, he wrote, “The prevalent impression made on the stranger’s mind by the Plains is one of loneliness – of isolation. You press on, day after day, without seeing a house, a fence, a cultivated field or even a forest.”1 Americans had been moving west since the earliest landings on the eastern coast of the country in the seventeenth century. By the turn of the nineteenth century, much of the land east of the Mississippi River had been settled and some areas had even been granted statehood in the union. Further expansion was affected by the political reality that territory west of the river was a matter of dispute: Spain, Britain, France and the new American republic all made their claims. When President Jefferson made the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, the conflicts were largely settled, and Americans had an open door to move west.

Yet, the right to settle was a different matter from the ability to do so. The journey of Lewis and Clark, the subject of the September illustration, demonstrated the difficult and daunting conquest of this territory. Commissioned by President Jefferson to explore the Louisiana Purchase, the Corps of Discovery had spent over two difficult years (1804-1806) on the trip to and from the Pacific coast, and afterwards, few Americans tried to penetrate the wilderness as Lewis and Clark had. All that land remained as it had been before the United States existed, and only a small number of intrepid individuals such as the mountain men roamed its expanse. It was not until the 1830s that any trans-Mississippi movement of a significant scale began.

When it did, one of N.C. Wyeth’s ancestors was a leader. Nathaniel Jarvis Wyeth (1802-1856) was a prosperous businessman from a long-established Massachusetts family. He had amplified his fortunes by his inventions for cutting and preserving ice which he cut from frozen ponds in the wintertime and then packed and sent abroad as far as the Caribbean. Despite all his success, however, he was moreinterested in the West. Other New Englanders shared his fascination, but he grew tired of waiting for someone to organize a trip and finally took it upon himself. He left Boston in the spring of 1832 and traveled to Independence, Missouri, a small town near present-day Kansas City which became the starting point for much of the Western migration. From there, he traced a route along the Platte River out onto the Great Plains where he observed about his surroundings, “The country appears desolate and dreary in the extreme[;] no one can conceive of the utter desolation of this region.”2 His goal, however, was to pass across those plains as quickly as possible and get to Oregon.

Wyeth’s idea was to take his share of the fur trade and set up a process for collecting and distributing pelts brought in by mountain men and trappers. He also saw an opportunity to establish a business drying the abundant salmon of the northwest coast, and then shipping the products to the eastern United States and elsewhere. Like Lewis and Clark, Wyeth’s trip was full of difficulties, including the desertion of most of the men who had signed up for the adventure. He arrived in Oregon in October of 1832, but his business plans failed, and he started back to the East. His travels homeward were also fraught with challenges but, undiscouraged, he determined to try again.3 By February of 1834, having organized a second enterprise for Oregon, he set off once more from Boston. For this trip, he had recruited more men and, in addition, was joined by Thomas Nuttall (1786-1859), a botanist and professor of natural history at Harvard, and John Kirk Townsend (1809-1851), an ornithologist. Both scientists had and would continue to travel the West, adding to the knowledge about its ecology. As before, Wyeth’s expedition across the continent was full of challenges, but this time he gained a better foothold in the Oregon Territory. Eventually, his fur trade company failed again, but not before he had thoroughly explored the Willamette Valley and other areas of the Pacific Northwest. He founded Ft. William on the Columbia River and Ft. Hall on the Snake River. After his return to Boston late in 1837, Wyeth never again attempted a western expedition. He was recognized, however, for helping to establish what would become the Oregon Trail, which was the primary route for western migration, and for fostering further interest in the settling of the Oregon Territory. Ft. Hall, near present day Pocatello, Idaho became one of the stops on the Trail. He was also often consulted on the Indian tribes of the lands he had explored.

Wyeth must have pointed out his ancestor’s connection to the Oregon Trail, since he was mentioned so prominently in the calendar page’s caption. The scene that he painted, however, is not the kind of travel that Nathaniel Wyeth experienced. Early explorers did not travel by covered wagon, but usually by horseback or more ideally, by water. As Lewis and Clark had shown, however, there was no waterway that would transport Easterners all the way across the country to the West. The Platte River was not navigable, the distance across the Continental Divide was long and hazardous (portage was not an option), and the west-flowing rivers were rife with rapids and falls. Going by land was the only way. An important factor in the development of a transcontinental route was the discovery of South Pass, a twenty mile-wide valley in Wyoming. First found in 1810, it was forgotten until rediscovered by the mountain man Jedediah Smith (1799-1831) in 1824. Though the existence of this Pass was communicated, it was the early 1830s before the first wagon trains began moving through it.

The number of pioneers on the Oregon Trail rose significantly after the Treaty of 1846 when Great Britain relinquished claims to the Oregon Territory and established the northwestern boundary between the United States and Canada. Between 1846 and 1869, it is estimated that 400,000 people traveled the Oregon Trail. The trail split in southwestern Idaho (often at Ft. Hall, founded by Nathaniel Wyeth) and some went on to Oregon while others headed south to California. But nearly everyone had theexperience that Wyeth illustrated of crossing the Great Plains. When the transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869, the use of the Oregon Trail began to decline.

Scenes of the West are very common in Wyeth’s work, and he was often called upon to illustrate Western stories and novels, such as James Fenimore Cooper’s series, The Leatherstocking Tales. Among his works which most relate to his 1940 calendar page are his illustrations for a 1925 edition of Francis Parkman’s classic, The Oregon Trail. One from that series, The Parkman Outfit, depicts a covered wagon on the Plains, led by men on horseback, against a large expanse of a cloud-strewn sky. Wyeth may have been thinking about his ancestor’s journeys along the Oregon Trail when he commented about these paintings, “’This title [The Oregon Trail ] has been much on my mind for several years....The Oregon Trail has always been deep in my blood. I feel very much stirred to interpret my dreams into pictures.’”4

Most of the wagon trains began their four to six month journeys in April or May to assure that they could cross the Great Plains and the western mountain ranges before winter set in. That timetable, however, meant that they had to endure the heat and dryness of the summer. Horace Greeley recalled the discomforts of that part of the trip. “Drought is, through each summer, the master scourge of the Plains. No rain – or next to none – falls on them from May till October. By day, hot suns bake them, by night, fierce winds sweep them; parching the earth to cavernous depths; withering the scanty vegetation, and causing fires to run wherever a thin vesture of dead herbage may have escaped the ravages of the previous summer.”5 Wyeth’s painting suggests the strong, unrelieved intensity of the summer sun by the yellowish ground and the almost flat white areas where the light strikes the canvas fronts of the wagons. The variety of the clouds above them – some cumulous, some stratus – suggest the strength of the wind and the instability of the weather, as do the storm clouds and rain on the horizon to the right. Out on this prairie, the pioneers have nothing to protect them from any of the forces of nature.

The settlers often spent months readying their wagons and their supplies for the trip. Some of the wagons were Conestogas, but mostly the pioneers used a lighter-weight wagon known as a prairie schooner.6 Generally, they were about eleven feet long by four feet wide and were used more for carrying cargo than passengers; many pioneers walked most the way. The wagon itself was made of wood with hoops (normally made of wood; sometimes metal) attached to the sides. A long piece of canvas, often oiled to make it water resistant, was then stretched over the top and the ends drawn up with a drawstring that could be tightened or loosened, as conditions dictated. Though not seen clearly in Wyeth’s illustration, both the inside and the outside of the wagon had hooks on which all sorts of tools and possessions were hung. As his painting shows, the wagons were usually drawn by a team of oxen, and a drover, whip in hand, walked on the left beside the animals to guide and drive them along.7 The trains did form themselves into long columns, as in the painting, but also, as the painting suggests, they spread out when they could to minimize the dust. As Wyeth’s prairie schooners roll across the prairie, they are clearly following the wheel tracks of previous wagon trains. It did not take long for the Oregon Trail to become well worn by the path taken by the hundreds of wagons that traversed it, and for many years after the great western migration, ruts could be seen where their wheels had left their marks in the earth.8

The portion of the westward trek shown by Wyeth is probably through Nebraska or southeastern Wyoming. Perhaps it is the long part of the Trail that followed the bed of the Platte River, a broad, generally shallow but unpredictable river whose water was muddy and not always fit to drink. The land surrounding the river held particular challenges because of its harshness and its length, as one traveler recalled. “The eager thousands pressing westward each summer to the shores of the Pacific find no relief from the length, the weariness, of their tedious journey....For weeks they stalk in dusty, sombre array, beside the broad, impetuous Platte; finding obstruction, not furtherance, in its rippling, treacherous current.”9 As they coursed their way toward the Pacific, pioneers often commented that the Plains were like an ocean that seemed to go on forever, featureless and crushing in its vastness. Even the term “prairie schooners” suggests the association with a grassland sea. When the writer Washington Irving (1783-1859) wrote about his “tour on the prairies” in 1835, he registered his own perception of the landscape. “The Far West broke upon us. An immense extent of grassy, undulating, or, as it is termed, rolling country, with here and there a clump of trees, dimly seen in the distance like a ship at sea; the landscape deriving sublimity from its vastness and simplicity.”10

Wyeth well captures that sense of the vastness and the overwhelming space of the ocean-like Great Plains. Even the thin line along the horizon resembles a distant sea, though we know that its obscuring color is only a function of the great distance. The pictorial problems of painting such flat and featureless plains have been daunting to many American painters, and when they have taken on this landscape, they have often emphasized, as Wyeth does here, the enormity of the sky.11 The skies in most of his paintings for America in the Making are dominant in the composition, full of variety and even drama. In Covered Wagons, the amount of space given in the composition to the sky may be intended to reflect the sensations of those who, step by step, moved across these geographic spaces. Many have characterized the crossing of the Plains as a dreary experience, and yet others have recognized that, for all its flat and unrelieved expanse, the landscape possesses a certain magnificence. Its openness, emptiness, and utter lack of shelter infuses the viewer with a sense of a self-sustained nature that exists and endures completely separate from humans. The very smallness of these figures and their households in this huge, nearly incomprehensible stretch of land and its endless sky affirms the achievement of having entered these Plains, grappled with them, and conquered them. As Americans in the late 1930s worried about the coming of World War II, this pioneer heritage might have seemed a source of national strength.

ENDNOTES

1 Greeley, Horace, “The Plains As I Crossed Them Ten Years Ago,” Harper’s Magazine, 1896, in An American Retrospective: Writing from Harper’s Magazine, 1850-1984, edited by Ann Marie Cunningham, New York: Harper’s Magazine Foundation, 1984, 90-94, 92.

2 Wyeth, Nathanial J., The Journals of Captain Nathaniel J. Wyeth, with the Wyeth Monograph on Pacific Northwest Indians Appended, Fairfield, Washington: Ye Galleon Press, 1969. Available on at http://www.xmission.com/~drudy/mtman/html/nwythint.html.

3 For an account of Wyeth’s Oregon expeditions, see http://www.mman.us/wyethnathaniel.htm.

4 Preface for Parkman, Francis, The Oregon Trail, Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1925; quoted in Podmaniczky, 481, I 1004 (332); The Parkman Outfit is I 1006 (315).

5 Greeley, “The Plains...,” 93.

6 Wyeth painted a number of covered wagons and western scenes during his career, but for this painting, his tax records show that he made research trips to Wilmington and Philadelphia. He also traveled to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania where, according to Podmaniczky, he likely visited J.C. Frey, a collector of Conestoga wagons. His studio held numerous photographs of wagons as well.

7 Horses were usually not hardy enough for the rigors of pulling a wagon that distance, and it was more difficult to feed them since they needed grain. Mules were an alternative to oxen, but the strength and low maintenance of oxen made them the preferred choice. In addition, oxen could be used to pull the plows that would break the ground on the new farms.

8 Evidence of the Oregon Trail can still be found in a number of places along the old route. Some the deepest ruts constitute a National Historic Landmark near Guernsey, Wyoming.

9 Greeley, “The Plains...,” 92. 10 Irving, Washington, A Tour on the Prairies, 1835; reprinted in The American Tradition in Literature, 4th edition, New York: Grosset and Dunlap, 1979, 522; available online at http://etext.virginia.edu/toc/modeng/public/IrvTour.html.

11 For an excellent study of this topic, see Kinsey, Joni L., Plain Pictures: Images of the American Prairie, Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian University Press and the University of Iowa Museum of Art, 1996.

Locations

- (not entered) Iowa State University, Brunnier Main Storage

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938

Object number: UM82.120

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938/1939

Object number: UM82.121

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938/1939

Object number: UM83.17

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1939

Object number: UM90.53

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938

Object number: UM83.16

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938

Object number: UM83.14

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938/1939

Object number: UM83.13

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938/1939

Object number: UM83.18

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938/1939

Object number: UM83.19

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938/1939

Object number: UM83.21

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938

Object number: UM83.20