America in the Making: Francisco Vasquez De Coronado

Object NamePainting

Artist / Maker

Newell Convers Wyeth

(American, 1882 - 1945)

Date1938

OriginU.S.A.

MediumOil on hardboard (Renaissance panel)

Dimensions26 3/4 × 24 7/8 in. (67.9 × 63.2 cm)

ClassificationsPaintings

Credit LineGift of John Morrell and Company, Ottumwa, Iowa. In the permanent collection, Brunnier Art Museum, University Museums, Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa.

CopyrightUniversity Museums, Iowa State University prohibits the copying or reproduction in any medium of materials on this website with the following exceptions: Iowa State University students, faculty, and staff for educational use in formal instruction, papers, presentations and projects; limited non-commercial; and personal use that meets the criteria for fair use as defined in the U.S. copyright laws.

Images from the University Museums’ collection cannot be used for publication, apparel/non-apparel merchandise, digital or commercial purposes without prior written permission from the University Museums, Iowa State University. Fair use does not apply to the extent that a license agreement or other contract controls reproduction or other use. University Museums and Iowa State University makes no representation that it is the owner of the copyright of the art object depicted in the photo materials and assumes no responsibility for any claims by third parties arising out of use of the photo materials. Users must obtain all other permissions required for usage of the art object and the photo materials.

For more information, please see http://www.museums.iastate.edu/ImageReproduction.html

Object numberUM83.20

Status

Not on viewCollections

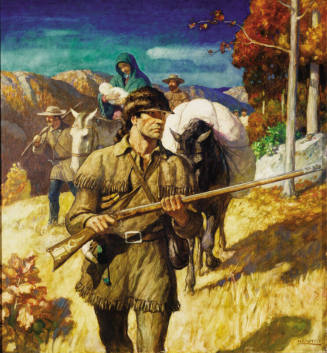

Label TextCoronado’s march (1540-1542) in search of the golden wealth of the fabulous “Seven Cities of Cibola” was the first expedition to penetrate the Central West of the United States. Traveling from the Mexican border through Taos, New Mexico and Western Texas, his army pushed as far north as the site of Great Bend, Kansas.

Wyeth’s first picture for the 1940 calendar depicts the Spanish explorer Francisco Vasquez de Coronado (1510-1554) who, exactly four hundred years earlier, had begun an expedition into the American Southwest where one of the discoveries was the Grand Canyon. The choice to begin the calendar with Coronado may have come about because 1940 was the 400th anniversary of his exploration of the American Southwest; the Post Office even issued a three cent stamp to commemorate the event. Starting out from Mexico in 1540, Coronado was determined to find the “golden cities” that reportedly gleamed somewhere to the north. What he found were the deserts, mountains, and plains in the area we now call Arizona and New Mexico, inhabited by indigenous peoples who had none of the riches he had hoped for. Continuing his search for treasure, Coronado then sought the fabled city of Quivira which, according to Indian accounts, was full of gold. Coronado wandered across the panhandles of what we now call Texas and Oklahoma and as far east as the central Kansas area, bringing back some of the earliest reports of the vast buffalo herds of the plains and the tribes who hunted them. In the end, however, Coronado realized that the reports of fantastic cities of wealth were false, and in 1542 he returned to Mexico in disgrace.

An alternative title to this painting is Coronado Starts for Quivira; The Plains Indians Never Saw Horses Until the Appearance of Spanish Explorers such as Coronado.1 This title emphasizes what the Spaniards brought into the territory rather than what they took from it. Horses had existed in pre-historic North America, but they had long been extinct there. Their re-introduction brought about major change in the tribal societies of the Great Plains and beyond. For example, hunters on horseback could more easily kill a running buffalo, thus increasing the food supply, along with all the other products the Indians derived from the buffalo. The nomadic Plains tribes also benefitted from the strength and mobility of horses as pack animals. Of course, much of the lore of the romantic West is based upon cowboys and Indians, all mounted on their trusty steeds.

Like other pictures in Wyeth’s series, the movement is east toward the west, suggesting that Coronado may be on his return trip, where his hopes for riches were disappointed.2 His route was north from Mexico and then to the east, and then back again southwest toward Mexico. The expedition was diverted westward for a time when, in the process of exploring the Colorado River, the Grand Canyon was discovered. Wyeth captures a sense of the enormity of Coronado’s enterprise as well the daunting character of much of the land they encountered. The relentless heat, the miles without water, and the weariness of searching through a hostile environment for illusionary wealth are all implied in Wyeth’s image. The soldier behind Coronado rides with his head down, and the horses (Coronado’s especially) stretch their necks down and outward as if straining to endure their march. Wyeth’s upward view monumentalizes the Spanish explorers to some extent, but they remain dwarfed by the scope and barrenness of the landscape surrounding them. The artist makes no attempt to illustrate the size of this expedition, which began with over 1500 participants, and the few figures included in this painting may suggest the drastic reduction in numbers of Coronado’s force. At the same time, in keeping with his general approach of focusing on individual heroes, Wyeth places Coronado front and center, still alert, still “tall in the saddle” (as befits a man in the Western landscape), and still with his eyes trained on the horizon. With the horses’ hooves stirring up the dust of the desert, bright light beats down from a huge sky as the travelers cross a vast, flat plain. The pace is slow, as suggested by the friar walking behind the front ranks. This figure may represent Fray Marcos de Niza, a Francisan friar who was among those who told Coronado stories he had heard about “golden cities” to the north. The inclusion of the friar recognizes the importance for the Spanish of propagating Christianity among the Indians and, in fact, Catholicism became a force in the formation of the character of the American Southwest.

To contemporary eyes, Wyeth’s interpretation is heavily Eurocentric, eliminating any reference to the Indians who played such a motivating role in this story. It was they who had first filled the Spaniards’ eyes with golden gleams as they told their tales of fantastic wealth, always to be found elsewhere. It is possible that the Indians told these stories in hopes of enticing the Spaniards away from the tribes’ territory. According to the Texas writer, J. Frank Dobie, in his classic book about the search for treasure in the Southwest, Coronado’s Children, it was always “mas alla” or “on beyond” as the Indians steered the Europeans across the trackless deserts and plains. 3 When Coronado’s expedition left Mexico, it was accompanied by a thousand Tlaxcalan Indians, and along the way, it encountered numerous tribes including the Zuni, Hopi, and Plains peoples such as the Comanche and the Wichita. None of these indigenous figures, however, are included in Wyeth’s picture, nor is the sometimes bloody progress of the expedition suggested. Coronado’s contacts with the tribes often resulted in battles with high Indian casualties. The Indian guide who led the expedition over the high plains up into the area we now call Kansas was executed when he admitted, under torture, that the “golden city” of Quivira was a lie. Coronado’s men also suffered great hardships during their journey from heat, cold, lack of potable water, and other difficulties. 4 Though the expedition succeeded as an historic exploration, Coronado (and his superiors back in Mexico) regarded it as a failure: the kinds of New World riches found by other Spanish explorers in Mexico and Peru were an illusion in the Southwest. Though Wyeth may be registering some sense of the expedition’s disappointment and weariness, his most important message is likely the heroism and adventure of Coronado’s quest.

The study for Coronado shows a composition very close to that of the painting, with the main difference in the sky, where the drawing has more stratus cloud formations. Three distinct banks of rectilinear cloud formations fill the sky, with one so close to the horizon that it could at first be mistaken for a line of distant mesas. Coronado’s upper body and head are placed between two horizontal stratus cloud banks so that his silhouette is sharply delineated. In the painting, Wyeth eliminated the complex cloud background to focus on a single large formation with a smaller one floating just above it. Coronado’s helmeted head is now placed against the lower section of the cloud, so that the isolation (and the pictorial emphasis) on his single figure is lessened.

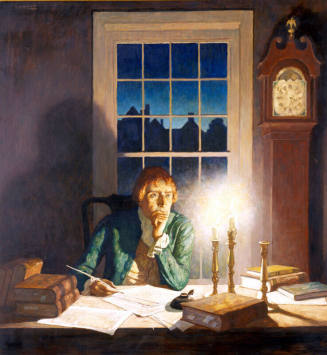

The drawing also has a strip of paper added at the top which constitutes approximately one fourth of the sheet. 5 Dimensions of all the drawings are similar so it seems unlikely that the strip was added to extend the size of the picture. It is possible that Wyeth added the length of paper to completely cover an earlier design. In only one other drawing, Benjamin Franklin, is paper added, and there it divides the composition almost exactly in half, vertically. That section contains an entire figure, making it appear that Wyeth desired a major change in his Franklin composition. As he worked out the placement of the clouds for Coronado, Wyeth probably added the strip to re-work that part of the composition on a blank section of paper.

His record of expenses for this particular painting (which added up to $91.80) indicates that he employed models and that he made a trip to the Metropolitan Museum of Art to study its collection of armor.6

ENDNOTES

1 The curator of the N.C. Wyeth Collection at the Brandywine River Museum, Christine B. Podmaniczky, has reason to believe that this secondary title was applied to this painting not by Wyeth, but by the Kansas Coronado Cuarto Centennial Commission. The Commission published a postcard of the painting, giving credit to the Morrell Company for its gift of the painting to Iowa State College. Podmaniczky to DeLong, July 8, 2010.

2 It may be tempting to read the image as one that incorporates Coronado’s disappointment or even a tone of defeat about the expedition. As pointed out by Podmaniczky, however, such a reading would be contrary to Wyeth’s usual practice and certainly inappropriate for a series on America in the Making. Podmaniczky to DeLong, July 8, 2010.

3 Dobie, J. Frank, Coronado’s Children: Tales of Lost Mines and Buried Treasures of the Southwest, New York: Grosset and Dunlap, 1930, vi-vii. The legend continues in the 1989 film, Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, in which the young Indiana begins his archaeological career with the discovery of “The Cross of Coronado.”

4 The story of the expedition was recorded later in 1596 by a member of the expedition, Pedro de Casteneda, in The journey of Coronado, 1540-1542, from the city of Mexico to the Grand Canyon of the Colorado and the buffalo plains of Texas, Kansas and Nebraska, as told by himself and his followers, translated and edited by George Parker Winship, New York: Allerton Book Co., 1922. Available on the PBS website, Archives of the West. http://www.pbs.org/weta/thewest/resources/archives/one/corona1.htm.

5 Images of the drawings come from lantern slides that Wyeth had made, not from the drawings themselves. Dimensions, therefore, are not known, though, based on Wyeth’s normal practice, the size of the drawings is likely quite similar to that of the paintings. The University Museums thanks Christine B. Podmaniczky for providing images of these lantern slides.

6 Collection and curatorial files of the N.C. Wyeth Collection of the Brandywine River Museum. The University Museums thanks Christine B. Podmaniczky for making these records available and for her extremely helpful comments.

Locations

- (not entered) Iowa State University, Brunnier Main Storage

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938

Object number: UM83.16

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1939

Object number: UM90.53

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938

Object number: UM83.14

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1939

Object number: UM83.15

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938/1939

Object number: UM83.18

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938/1939

Object number: UM83.19

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938/1939

Object number: UM83.21

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938/1939

Object number: UM83.13

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938/1939

Object number: UM83.17

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938

Object number: UM82.120

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938/1939

Object number: UM82.121