America in the Making: The Mayflower Compact

Object NamePainting

Artist / Maker

Newell Convers Wyeth

(American, 1882 - 1945)

Date1938/1939

OriginU.S.A.

MediumOil on hardboard (Renaissance Panel)

Dimensions26 3/4 × 24 7/8 in. (67.9 × 63.2 cm)

ClassificationsPaintings

Credit LineGift of John Morrell and Company, Ottumwa, Iowa. In the permanent collection, Brunnier Art Museum, University Museums, Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa.

CopyrightUniversity Museums, Iowa State University prohibits the copying or reproduction in any medium of materials on this website with the following exceptions: Iowa State University students, faculty, and staff for educational use in formal instruction, papers, presentations and projects; limited non-commercial; and personal use that meets the criteria for fair use as defined in the U.S. copyright laws.

Images from the University Museums’ collection cannot be used for publication, apparel/non-apparel merchandise, digital or commercial purposes without prior written permission from the University Museums, Iowa State University. Fair use does not apply to the extent that a license agreement or other contract controls reproduction or other use. University Museums and Iowa State University makes no representation that it is the owner of the copyright of the art object depicted in the photo materials and assumes no responsibility for any claims by third parties arising out of use of the photo materials. Users must obtain all other permissions required for usage of the art object and the photo materials.

For more information, please see http://www.museums.iastate.edu/ImageReproduction.html

Object numberUM83.21

Status

Not on viewCollections

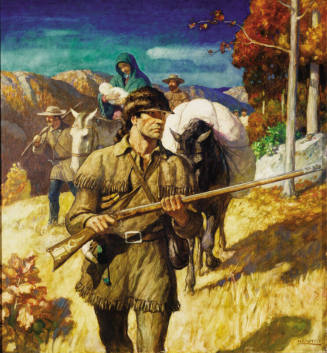

Label TextThis historic document, which was drawn up and signed by the Pilgrims aboard ship on November 11, 1620, gave a certain semblance of legality to their government which appealed to their English respect for law and order. In the group are John Carver, William Bradford, Miles Standish and John Alden.

The Mayflower Compact was an agreement among the Pilgrims and other passengers about the government they would have as they founded the Plymouth colony in 1620, the second permanent English settlement in North America (The first was in Jamestown, Virginia in 1607.). As Wyeth’s painting for February depicts, it was signed even before they disembarked from the Mayflower, the ship that brought them across the Atlantic Ocean from England. The document was intended to organize the voyagers into “a Civil Body Politic, for our better ordering and preservation” and to ensure that the voyagers would work together “for the general good of the Colony.” The religious group known as the Pilgrims constituted about half of the slightly over one hundred passengers on the Mayflower, the others being skilled workers (such as John Alden, a cooper, or barrel-maker), servants, and others. Called “strangers” by the Pilgrims, this group had varying reasons for making the voyage and, over the course of the journey, some had made it clear that they might pursue their own individual inclinations once they set foot on shore.

The problem arose partly because the Mayflower landed at what we now call Massachusetts, well north of its intended destination. The authority for the Pilgrims to found their colony came from the Virginia Company, a business chartered by King James I of England in 1606 for the purpose of establishing profitable colonies on the eastern coast of America. The Company’s first permanent colony had been at Jamestown, and the Pilgrims’ colony was to be at least a hundred miles north. Because they were not exactly where they planned to be, their “patent” or authorization was technically invalid, as the strangers recognized. Therefore, a compact was drawn up to address the situation. One of the Pilgrims, William Bradford, later wrote a history of the Plymouth Colony, recording the Compact and explaining why it was necessary. “I shall...begin with a [compact] made by them before they came ashore; being the first foundation of their government in this place. Occasioned partly by the discontented and mutinous speeches that some of the strangers amongst them had let fall from them in the ship: That when they came ashore they would use their own liberty, for none had power to command them, the patent they had being for Virginia and not for New England...with which the Virginia Company had nothing to do.”1 It was also believed that, considering their changed circumstances, a new governing agreement “might be as firm as any patent, and in some respects more sure.”2 The agreement that they drew up was short and had only two provisions: that the signers would constitute a coherent governing group with the goal of creating a successful, orderly colony, and that they could create laws that would benefit everyone in the colony.3 Having signed the document, the group chose one of the Pilgrims, John Carver, to be their governor for a year.

The Pilgrims were so called because they embarked on a long trip largely for religious reasons; others on the Mayflower had no such notion. The Pilgrims were part of a larger English religious group known as the Puritans who had separated from the Church of England partly in protest against what they regarded as excesses. Aside from political issues, the Puritans believed in simplicity: of dress, of demeanor, and of religious practice. They wished to purify the practice of religion and eliminate worldly concerns that took the focus off Godly behavior. They rejected the idea of priests or bishops being the sole religious authority and believed that all worshippers had equal access to God. They gained considerable political power in England, but by the early 17th century, persecution began to be felt. One of the more extreme factions, known as the Separatists, finally left England for Holland where they enjoyed religious freedom for over a decade. They began to feel, however, that their children were being too influenced by the Dutch culture, and so they determined to move to the New World. After securing their charter from the Virginia Company, they set sail in the Mayflower in September of 1620.

After a harrowing journey of two months crossing the Atlantic, they arrived at Cape Cod Bay, Massachusetts early in November. Winter was approaching, and rather than continuing to sail along the coast line, they decided to go ashore. The next period of the voyagers’ adventure was what Bradford called the “Starving Time,” when half of their number died and the survival of the colony was in the hands of just a few who remained healthy. “That which was most sad and lamentable was, that in two or three months’ time half of their company died, especially in January and February, being the depth of winter, and wanting houses and other comforts....4 So as there died sometimes two or three of a day...that of 100 and some odd persons, scarce fifty remained. And of these, in the time of most distress, there was but six or seven sound persons who...spared no pains night nor day, but with abundance of toil and hazard of their own health, fetched them wood, made them fires, ...washed their loathsome clothes....In a word, did all the homely and necessary offices for them which dainty and queasy stomachs cannot endure to hear named.”5 The Pilgrims soon made contact with the Indians of the region, two of whom, Samoset and Squanto, taught them the rudiments of survival in the new land and how to maintain their food supply. In November of the following year, the Pilgrims invited the Indians to a feast, an event that became the American holiday of Thanksgiving.

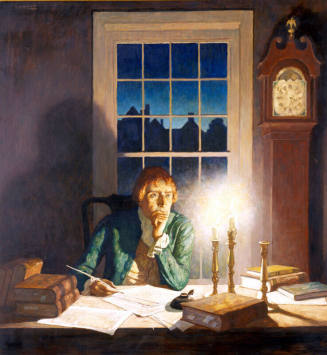

Wyeth’s painting depicts the signing of the Compact in the narrow, dark great cabin of the Mayflower. The low ceiling and the stark roughness of the ship’s timbers reflect the reality of the voyagers’ environment during the two-month trip from England. The room was likely about 13 by 17 feet and had only four windows.6 In the painting, light flows in from the west, perhaps suggesting the position of the new land relative to the Old World. The caption for the painting names four men, all of whom played prominent roles in the history and lore of the Plymouth Colony. The man bending over the plain chest may be John Carver (c.1576-1621), the first to sign the document, who helped arrange the voyage to America and was chosen the colony’s first governor. Recorded by Bradford as “a man godly and well approved among them,”7 Carver died the following April and was succeeded as governor by William Bradford.8

Bradford (1590-1657), the historian of the Plymouth Colony, served as governor for most of the next thirty years until his death, and he may be the figure dressed in blue and sitting on the only chair. Carver was actually nearly fifteen years older than Bradford, but Wyeth may have depicted Bradford as the elder of the group, considering his long life and service to the Pilgrim community. His prominence in the composition also suggests his significance for the Plymouth Colony.9 The man dressed in military garb behind Bradford is certainly Captain Miles Standish, a soldier by profession who was in charge of the defense of the Colony. Standish led the earliest encounters with the Indians and later, negotiated with them and on several occasions fought them. The man standing with the inkwell in his hand may be John Alden (1599-1687), who was not a Puritan, but who was hired as a craftsman for the group. He served as assistant to the governor from 1653 to 1675 and, with Standish, founded the Massachusetts town of Duxbury. These two men are the protagonists in a famous American poem written in 1858 by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, “The Courtship of Miles Standish.” In the poem, Standish decides to ask a young woman, Priscilla Mullin, to marry him. Lacking the confidence to ask her himself, he enlists the help of his friend, John Alden, to tell Priscilla of Captain Standish’s wish. Priscilla’s affections have actually settled on John Alden and, when he presents (with reluctance) Standish’s entreaty, she replies, “Why don’t you speak for yourself, John?”10 Like Standish and Alden, Priscilla was a real person: she was the only survivor in her family after her father, mother, brother, and the family’s servant died in the first winter. Priscilla Mullin and John Alden did marry and became the parents of eleven children.

Most of the other men arranged around the signers are dressed somberly in Pilgrim costume with their high-crowned hats. The Puritans dressed plainly, often in black, but also in other colors such as the russet jacket worn by the Pilgrim man in the left background. Nearly any color could be worn, as long as it was not of a flamboyant shade and the fabric was not fancy. The most important thing in their dress was its lack of ornamentation such as elaborate buttons or feathers in their hats.11 The man in the white shirt and soft, red hat may be one of the other workers employed for the voyage or one of the sailors. His presence perhaps suggests the egalitarian character of the group and the opportunities afforded to the common man by the colonies. Women are part of the group, but only as onlookers, not signers. Like most women of the period, they would not have had the legal standing to sign this or most other documents. Wyeth’s inclusion of them, however, emphasizes that they shared in the trials of the colonial experience and played an important role in the ultimate success of the colony. These Pilgrim women, along with Sacagawea in Lewis and Clark (September) and those with Daniel Boone, are the only women depicted in America in the Making.

According to his records, Wyeth hired twelve models for his pictures, rented costumes, and traveled to Philadelphia and Wilmington, probably to visit museums and other collections for sources for his image.12

ENDNOTES

1 Bradford, William, Of Plymouth Plantation, 1620-1647, edited by Samuel Eliot Morison, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1966, 75. Another source of information about the early days of the colony is Mourt’s Relation: Journal of the Plantation at Plymouth, published in London in 1622 and written by Edward Winslow and William Bradford. The original Mayflower Compact signed on the Mayflower is lost, but Bradford made a copy of it in his history of the colony. Bradford’s manuscript descended through his family until it was deposited in the New England Library at the Old South Meeting House in Boston. By the end of the Revolutionary War (1775-1783), the manuscript was missing from the library, perhaps stolen while the house was used as a British garrison. It reappeared in London in the mid-19th century and, through long and complex negotiations, was eventually returned to Boston in 1897. Today, it is housed in the Massachusetts State Library. See the section “History of a History” in the Introduction by Morison in Bradford, xxvii-xl.

2 Bradford, 75.

3 The entire document reads (in modern style): “In the Name of God, Amen. We whose names are underwritten, the loyal subjects of our dread Sovereign Lord King James, by the Grace of God Great Britain, France, and Ireland King, Defender of the Faith, etc.[sic]. Having undertaken, for the Glory of God and advancement of the Christian Faith and Honour of our King and Country, a Voyage to plant the First Colony in the Northern Parts of Virginia, do by these presents solemnly and mutually in the presence of God and one of another, Covenant and Combine ourselves together into a Civil Body Politic, for our better ordering and preservation and furtherance of the ends aforesaid; and by virtue hereof to enact, constitute and frame such just and equal Laws, Ordinances, Acts, Constitutions and Offices, from time to time, as shall be thought most meet and convenient for the general good of the Colony, unto which we promise all due submission and obedience. In witness whereof we have hereunder subscribed our names at Cape Cod, the 11th of November, in the year of the reign of our Sovereign Lord King James, of England, France and Ireland the eighteenth, and of Scotland the fifty-fourth. Anno Domini 1620.” Bradford, 76. The document can also be accessed online in numerous places, including the site for the Avalon Project of the Goldman Law Library at Yale University: http://avalon.law.yale.edu/17th_century/mayflower.asp. This site also lists the names of all the signers.

4 Without enough shelters on shore, many of the voyagers had to continue living on the Mayflower.

5 Bradford, 77.

6 Philbrick, Nathanial, Mayflower: A Story of Courage, Community and War, New York: Penguin Group, 2006, 43. According to Philbrick, the Mayflower had “two windows in the stern and one on either side.” Other estimates of the size of the great cabin are that it was 15 by 25 feet “at its largest” and that the main deck was 75 by 20 “at most. Below decks anybody five feet tall could never stand fully upright.” Caffrey, Kate, The Mayflower, New York: Stein and Day, 1974. See also Gill, Crispin, Mayflower Remembered, New York: Taplinger Publishing Co., 1970, 65-67. Estimates of the overall size of the ship are about 90 feet long and 26 feet broad. The actual ship returned to England in April of 1621 and continued in service until it was broken up.

7 Bradford, 75.

8 Bradford, 86.

9 Were it not for Wyeth’s caption, this elderly figure might be identified as William Brewster (c.1566-1644), one of the oldest and most well-regarded among the Pilgrim men.

10 Longfellow’s poem can be accessed online at the Maine Historical Society website: http://www.longfellow.org/poems_poems.php?pid=186.

11 Tortura, Phyllis G. and Eubank, Keith, Survey of Historic Costume, 4th edition, New York: Fairchild Publications, 2005, 202. See also Warwick, Edward and Wyckoff, Alexander, Early American Dress: The Colonial and Revolutionary Periods, New York: Benjamin Blom, 1965, 96.

12 Curatorial files of the Brandywine River Museum.

Locations

- (not entered) Iowa State University, Brunnier Main Storage

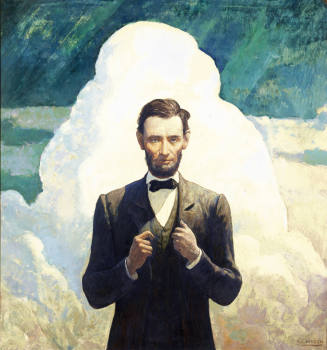

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1939

Object number: UM90.53

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938/1939

Object number: UM83.19

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938

Object number: UM83.16

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938/1939

Object number: UM83.13

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938

Object number: UM83.14

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938/1939

Object number: UM83.18

Object Name: Coffee can and Saucer

Sèvres Porcelain Manufactory

1789

Object number: 2.7.3ab

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938

Object number: UM82.120

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938/1939

Object number: UM82.121

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1938/1939

Object number: UM83.17

Object Name: Painting

Newell Convers Wyeth

1939

Object number: UM83.15